Wednesday, March 28, 2007

An e-mail to my new cardiologist

Hi Dr. DeVries,

I am excited about the article in the NEJM regarding angioplasty. I guess it validates the decision I made to put my faith in Dr. Wayne three years ago.

I learned a couple of weeks ago that my Tricare health insurance coverage has changed because I stopped paying for my Medicare Part B when I finally thought I was off of Social Security disability last year. Well, it seems my Medicare was only suspended so I have to wait until July before I am covered again. I will be paying cash for my medical care until then. If I drive to Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, I can be seen by a military doctor and get my meds filled for free.

I haven't started the Crestor yet and after talking to the Space Doctor (http://www.spacedoc.net) , a former astronaut who has written about statins a lot, I probably won't fill the prescription. I have been looking into EECP and am arranging an adequate amount of time off to receive it. I will probably start the 7 week course in August.

The combination of the isosorbide and NTG pretty much control my angina. Since my visit with you on the 8th, I go some days without any angina at all. I have been watching my diet, no refined sugars and six small meals a day, including a lot of fresh veggies and fruits. I've had oatmeal every morning since returning to Nigeria. I test my blood sugar every morning and three times on Tuesdays and Saturdays. It's been normal.

I guess that's about it from here. See you in June.

Jeff

I am excited about the article in the NEJM regarding angioplasty. I guess it validates the decision I made to put my faith in Dr. Wayne three years ago.

I learned a couple of weeks ago that my Tricare health insurance coverage has changed because I stopped paying for my Medicare Part B when I finally thought I was off of Social Security disability last year. Well, it seems my Medicare was only suspended so I have to wait until July before I am covered again. I will be paying cash for my medical care until then. If I drive to Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio, I can be seen by a military doctor and get my meds filled for free.

I haven't started the Crestor yet and after talking to the Space Doctor (http://www.spacedoc.net) , a former astronaut who has written about statins a lot, I probably won't fill the prescription. I have been looking into EECP and am arranging an adequate amount of time off to receive it. I will probably start the 7 week course in August.

The combination of the isosorbide and NTG pretty much control my angina. Since my visit with you on the 8th, I go some days without any angina at all. I have been watching my diet, no refined sugars and six small meals a day, including a lot of fresh veggies and fruits. I've had oatmeal every morning since returning to Nigeria. I test my blood sugar every morning and three times on Tuesdays and Saturdays. It's been normal.

I guess that's about it from here. See you in June.

Jeff

The NEJM Article

For those who want to read the article regarding the angioplasty study in the NEJM, here is a link:

NEJM

NEJM

Tuesday, March 27, 2007

New Study Validates the Premise of this Blog

According to an Associated Press report, More than half a million people a year with chest pain are getting an unnecessary or premature procedure to unclog their arteries because drugs are just as effective, suggests a landmark study that challenges one of the most common practices in heart care.

The stunning results found that angioplasty did not save lives or prevent heart attacks in non-emergency heart patients.

An even bigger surprise: Angioplasty gave only slight and temporary relief from chest pain, the main reason it is done.

"By five years, there was really no significant difference" in symptoms, said Dr. William Boden of

Buffalo General Hospital in New York. "Few would have expected such results."

He led the study and gave results Monday at a meeting of the American College of Cardiology. They also were published online by the New England Journal of Medicine' name=c1> SEARCHNews News Photos Images Web' name=c3> New England Journal of Medicine and will be in the April 12 issue.

Angioplasty remains the top treatment for people having a heart attack or hospitalized with worsening symptoms. But most angioplasties are done on a non-emergency basis, to relieve chest pain caused by clogged arteries crimping the heart's blood supply.

Those patients now should try drugs first, experts say. If that does not help, they can consider angioplasty or bypass surgery, which unlike angioplasty, does save lives, prevent heart attacks and give lasting chest pain relief.

In the study, only one-third of the people treated with drugs ultimately needed angioplasty or a bypass.

"You are not putting yourself at risk of death or heart attack if you defer," and considering the safety worries about heart stents used to keep arteries open after angioplasty, it may be wise to wait, said Dr. Steven Nissen, a Cleveland Clinic heart specialist and president of the College of Cardiology.

Why did angioplasty not help more?

It fixes only one blockage at a time whereas drugs affect all the arteries, experts said. Also, the clogs treated with angioplasty are not the really dangerous kind.

"Even though it goes against intuition, the blockages that are severe that cause chest pain are less likely to be the source of a heart attack than segments in the artery that are not severely blocked," said Dr. David Maron, a Vanderbilt University cardiologist who helped lead the new study.

Drugs are better today than they used to be, and do a surprisingly good job, said Dr. Elizabeth Nabel, director of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

"It may not be as bad as we thought" to leave the artery alone, she said.

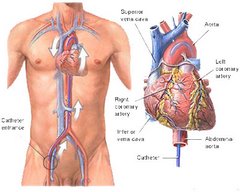

About 1.2 million angioplasties are done in the United States each year. Through a blood vessel in the groin, doctors snake a tube to a blocked heart artery. A tiny balloon is inflated to flatten the clog and a mesh scaffold stent is usually placed.

The procedure already has lost some popularity because of emerging evidence that popular drug-coated stents can raise the risk of blood clots months later. The new study shifts the argument from which type of stent to use to whether to do the procedure at all.

It involved 2,287 patients throughout the U.S. and Canada who had substantial blockages, typically in two arteries, but were medically stable. They had an average of 10 chest pain episodes a week — moderately severe. About 40 percent had a prior heart attack.

"We deliberately chose to enroll a sicker, more symptomatic group" to give angioplasty a good chance to prove itself, Boden said.

All were treated with medicines that improve chest pain and heart and artery health such as aspirin, cholesterol-lowering statins, nitrates, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers. All also were counseled on healthy lifestyles — diet, exercise and smoking cessation.

Half of the participants also were assigned to get angioplasty.

After an average of 4 1/2 years, the groups had similar rates of death and heart attack: 211 in the angioplasty group and 202 in the medication group — about 19 percent of each.

Heart-related hospitalization rates were similar, too.

Neither treatment proved better for any subgroups like smokers, diabetics, or older or sicker people.

At the start of the study, 80 percent had chest pain. Three years into it, 72 percent of the angioplasty group was free of this symptom as was 67 percent of the drug group.

That means you would have to give angioplasties to 20 people for every one whose chest pain was better after three years — an unacceptably high ratio, Nissen said.

After five years, 74 percent of the angioplasty group and 72 percent of the medication group were free of chest pain - "no significant difference," Boden said.

The study was funded by the U.S.

Department of Veterans Affairs' name=c1> SEARCHNews News Photos Images Web' name=c3> Department of Veterans Affairs, the Medical Research Council of Canada and a host of drug companies. Stent makers refused to help pay for the research, said scientists who led the study.

The study renewed a heated animosity between doctors who perform angioplasty and other heart specialists.

In fact, one who does the procedures and who spoke at a meeting in New Orleans sponsored by stent maker Boston Scientific Corp. was responsible for the early release of the study's results, which were not due out until Tuesday.

The study "was rigged to fail, and it did," the Wall Street Journal quoted Dr. Martin B. Leon of Columbia University telling several hundred of his colleagues Sunday night.

"A lot of people have been taking shots at us, and we need to go on the offense for awhile," the Journal reported Leon said.

He claimed to have inside knowledge of the results because he reviewed the study for the New England Journal. The journal would not comment, saying the identity of its reviewers is confidential.

The cardiology college issued a statement saying it was "extremely disappointed" results were released prematurely, "betraying the confidentiality of the scholarly process and the professional integrity of the scientific community."

The college "will be considering strong sanctions against the individual or individuals involved," the statement said.

Boston Scientific shares fell $1.05, or 6.6 percent, to close at $14.22 on the

New York Stock Exchange' name=c1> SEARCHNews News Photos Images Web' name=c3> New York Stock Exchange at double their average volume.

Dr. Spencer King of Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta, a leading cardiologist who does many angioplasties, said he was disappointed in the study results.

"How many patients have interventions in which the only expectation is to reduce the use of nitroglycerin or to walk a bit faster? Most patients anticipate a better prognosis and might opt for an extended course of medical therapy if they believe they are not putting their life at excess risk," he wrote in a recent editorial in an

American Heart Association' name=c1> SEARCHNews News Photos Images Web' name=c3> American Heart Association journal.

In an interview at the cardiology meeting, King said he recently had surgery for back pain and did not expect permanent relief but added, "If it only held up for five years, I wouldn't be happy about it."

The new study "should lead to changes in the treatment of patients with stable coronary artery disease, with expected substantial health care savings," Dr. Judith Hochman of New York University wrote in an editorial in the journal.

An angioplasty costs roughly $40,000. The drugs used in the study are almost all available in generic form.

Maron, the Vanderbilt doctor who helped lead the study, said people should give the drugs a chance.

"Often I think that patients are under the impression that unless they have that procedure done, they're not getting the best of care and are at increased risk of having a heart attack and die," he said.

Dr. Raymond Gibbons, a Mayo Clinic cardiologist and American Heart Association president, agreed: "This trial shows convincingly that that assumption is incorrect."

___

The stunning results found that angioplasty did not save lives or prevent heart attacks in non-emergency heart patients.

An even bigger surprise: Angioplasty gave only slight and temporary relief from chest pain, the main reason it is done.

"By five years, there was really no significant difference" in symptoms, said Dr. William Boden of

Buffalo General Hospital in New York. "Few would have expected such results."

He led the study and gave results Monday at a meeting of the American College of Cardiology. They also were published online by the New England Journal of Medicine' name=c1> SEARCHNews News Photos Images Web' name=c3> New England Journal of Medicine and will be in the April 12 issue.

Angioplasty remains the top treatment for people having a heart attack or hospitalized with worsening symptoms. But most angioplasties are done on a non-emergency basis, to relieve chest pain caused by clogged arteries crimping the heart's blood supply.

Those patients now should try drugs first, experts say. If that does not help, they can consider angioplasty or bypass surgery, which unlike angioplasty, does save lives, prevent heart attacks and give lasting chest pain relief.

In the study, only one-third of the people treated with drugs ultimately needed angioplasty or a bypass.

"You are not putting yourself at risk of death or heart attack if you defer," and considering the safety worries about heart stents used to keep arteries open after angioplasty, it may be wise to wait, said Dr. Steven Nissen, a Cleveland Clinic heart specialist and president of the College of Cardiology.

Why did angioplasty not help more?

It fixes only one blockage at a time whereas drugs affect all the arteries, experts said. Also, the clogs treated with angioplasty are not the really dangerous kind.

"Even though it goes against intuition, the blockages that are severe that cause chest pain are less likely to be the source of a heart attack than segments in the artery that are not severely blocked," said Dr. David Maron, a Vanderbilt University cardiologist who helped lead the new study.

Drugs are better today than they used to be, and do a surprisingly good job, said Dr. Elizabeth Nabel, director of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute.

"It may not be as bad as we thought" to leave the artery alone, she said.

About 1.2 million angioplasties are done in the United States each year. Through a blood vessel in the groin, doctors snake a tube to a blocked heart artery. A tiny balloon is inflated to flatten the clog and a mesh scaffold stent is usually placed.

The procedure already has lost some popularity because of emerging evidence that popular drug-coated stents can raise the risk of blood clots months later. The new study shifts the argument from which type of stent to use to whether to do the procedure at all.

It involved 2,287 patients throughout the U.S. and Canada who had substantial blockages, typically in two arteries, but were medically stable. They had an average of 10 chest pain episodes a week — moderately severe. About 40 percent had a prior heart attack.

"We deliberately chose to enroll a sicker, more symptomatic group" to give angioplasty a good chance to prove itself, Boden said.

All were treated with medicines that improve chest pain and heart and artery health such as aspirin, cholesterol-lowering statins, nitrates, ACE inhibitors, beta-blockers and calcium channel blockers. All also were counseled on healthy lifestyles — diet, exercise and smoking cessation.

Half of the participants also were assigned to get angioplasty.

After an average of 4 1/2 years, the groups had similar rates of death and heart attack: 211 in the angioplasty group and 202 in the medication group — about 19 percent of each.

Heart-related hospitalization rates were similar, too.

Neither treatment proved better for any subgroups like smokers, diabetics, or older or sicker people.

At the start of the study, 80 percent had chest pain. Three years into it, 72 percent of the angioplasty group was free of this symptom as was 67 percent of the drug group.

That means you would have to give angioplasties to 20 people for every one whose chest pain was better after three years — an unacceptably high ratio, Nissen said.

After five years, 74 percent of the angioplasty group and 72 percent of the medication group were free of chest pain - "no significant difference," Boden said.

The study was funded by the U.S.

Department of Veterans Affairs' name=c1> SEARCHNews News Photos Images Web' name=c3> Department of Veterans Affairs, the Medical Research Council of Canada and a host of drug companies. Stent makers refused to help pay for the research, said scientists who led the study.

The study renewed a heated animosity between doctors who perform angioplasty and other heart specialists.

In fact, one who does the procedures and who spoke at a meeting in New Orleans sponsored by stent maker Boston Scientific Corp. was responsible for the early release of the study's results, which were not due out until Tuesday.

The study "was rigged to fail, and it did," the Wall Street Journal quoted Dr. Martin B. Leon of Columbia University telling several hundred of his colleagues Sunday night.

"A lot of people have been taking shots at us, and we need to go on the offense for awhile," the Journal reported Leon said.

He claimed to have inside knowledge of the results because he reviewed the study for the New England Journal. The journal would not comment, saying the identity of its reviewers is confidential.

The cardiology college issued a statement saying it was "extremely disappointed" results were released prematurely, "betraying the confidentiality of the scholarly process and the professional integrity of the scientific community."

The college "will be considering strong sanctions against the individual or individuals involved," the statement said.

Boston Scientific shares fell $1.05, or 6.6 percent, to close at $14.22 on the

New York Stock Exchange' name=c1> SEARCHNews News Photos Images Web' name=c3> New York Stock Exchange at double their average volume.

Dr. Spencer King of Piedmont Hospital in Atlanta, a leading cardiologist who does many angioplasties, said he was disappointed in the study results.

"How many patients have interventions in which the only expectation is to reduce the use of nitroglycerin or to walk a bit faster? Most patients anticipate a better prognosis and might opt for an extended course of medical therapy if they believe they are not putting their life at excess risk," he wrote in a recent editorial in an

American Heart Association' name=c1> SEARCHNews News Photos Images Web' name=c3> American Heart Association journal.

In an interview at the cardiology meeting, King said he recently had surgery for back pain and did not expect permanent relief but added, "If it only held up for five years, I wouldn't be happy about it."

The new study "should lead to changes in the treatment of patients with stable coronary artery disease, with expected substantial health care savings," Dr. Judith Hochman of New York University wrote in an editorial in the journal.

An angioplasty costs roughly $40,000. The drugs used in the study are almost all available in generic form.

Maron, the Vanderbilt doctor who helped lead the study, said people should give the drugs a chance.

"Often I think that patients are under the impression that unless they have that procedure done, they're not getting the best of care and are at increased risk of having a heart attack and die," he said.

Dr. Raymond Gibbons, a Mayo Clinic cardiologist and American Heart Association president, agreed: "This trial shows convincingly that that assumption is incorrect."

___

Monday, March 26, 2007

Victims of Statins

More Testimony from Victim of Statins

"Since my husband, a previously alert and healthy man, started taking Atorvastatin, our lives have changed horrendously for the worse,'' writes a lady from Middlesex, echoed by others troubled variously by loss of memory, irritability, lethargy, personality change, melancholy, insomnia, excruciating muscle pains, numbness and burning of the hands and feet, bowel disturbances and much more.

There is no doubt that statins are to blame , as the improvement in in those who have "given them a rest'' verges on the miraculous.

"I felt like an old man of 90 and had to use a walking stick,'' writes a formerly very fit ex-Marine from Dorset, who has since returned to his thrice-weekly workout in the gym.

If you are concerned about statins, see the website of Florida physician (and former Nasa astronaut) Duane Gravelin, www.spacedoc.net,) where he has posted the experience of several hundred statin victims.

Next, you need to know two important facts that together would reduce the number of statin prescriptions by 70 per cent.

First, the cholesterol level in those who are otherwise fit and well (the vast majority of those on statins) is a weak predictor of heart disease. This particularly applies to those aged 65 or over, in whom there is an inverse relationship, according to a study in The Lancet five years ago, so that the lower the cholesterol the higher the risk of "all-cause mortality''.

The pounds 1 billion a year spent on statins would pay 70,000 more nurses. That shows the extravagance of this current medical enthusiasm where family doctors get a financial incentive to turn the fit and healthy into forgetful cripples.

If you want to look after your heart, buy a dog and have a pre-prandial whisky every evening.

"Since my husband, a previously alert and healthy man, started taking Atorvastatin, our lives have changed horrendously for the worse,'' writes a lady from Middlesex, echoed by others troubled variously by loss of memory, irritability, lethargy, personality change, melancholy, insomnia, excruciating muscle pains, numbness and burning of the hands and feet, bowel disturbances and much more.

There is no doubt that statins are to blame , as the improvement in in those who have "given them a rest'' verges on the miraculous.

"I felt like an old man of 90 and had to use a walking stick,'' writes a formerly very fit ex-Marine from Dorset, who has since returned to his thrice-weekly workout in the gym.

If you are concerned about statins, see the website of Florida physician (and former Nasa astronaut) Duane Gravelin, www.spacedoc.net,) where he has posted the experience of several hundred statin victims.

Next, you need to know two important facts that together would reduce the number of statin prescriptions by 70 per cent.

First, the cholesterol level in those who are otherwise fit and well (the vast majority of those on statins) is a weak predictor of heart disease. This particularly applies to those aged 65 or over, in whom there is an inverse relationship, according to a study in The Lancet five years ago, so that the lower the cholesterol the higher the risk of "all-cause mortality''.

The pounds 1 billion a year spent on statins would pay 70,000 more nurses. That shows the extravagance of this current medical enthusiasm where family doctors get a financial incentive to turn the fit and healthy into forgetful cripples.

If you want to look after your heart, buy a dog and have a pre-prandial whisky every evening.

Friday, March 16, 2007

Enhanced External Counterpulsation

Yet another weapon in the noninvasive armory against stable angina and coronary artery disease -- EECP.

What is EECP?

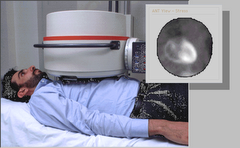

EECP is a mechanical procedure in which long inflatable cuffs (like blood pressure cuffs) are wrapped around both of the patient’s legs. While the patient lies on a bed, the leg cuffs are inflated and deflated with each heartbeat. This is accomplished by means of a computer, which triggers off the patient’s ECG so that the cuffs deflate just as each heartbeat begins, and inflate just as each heartbeat ends.

When the cuffs inflate they do so in a sequential fashion, so that the blood in the legs is “milked” upwards, toward the heart.

EECP has two potentially beneficial actions on the heart. First, the milking action of the leg cuffs increases the blood flow to the coronary arteries. (The coronary arteries, unlike other arteries in the body, receive their blood flow after each heartbeat instead of during each heartbeat. EECP, effectively, “pumps” blood into the coronary arteries.) Second, by its deflating action just as the heart begins to beat, EECP creates something like a sudden vacuum in the arteries, which reduces the work of the heart muscle in pumping blood into the arteries. Both of these actions have long been known to reduce cardiac ischemia (the lack of oxygen to the heart muscle) in patients with coronary artery disease. Indeed, an invasive procedure that does the same thing, intra-aortic counterpulsation (IACP, in which a balloon-tipped catheter is positioned in the aorta, which then inflates and deflates in time with the heartbeat), has been in widespread use in intensive care units for decades, and its effectiveness in stabilizing extremely unstable patients is well known.

While a primitive form of external counterpulsation has also been around for a long time, it has not been very effective until recently. Thanks to new computer technology that allows the perfect timing of the inflation and deflation of the cuffs, and produces the milking action, modern EECP has been greatly enhanced.

EECP is administered as a series of outpatient treatments. Patients receive 5 one-hour sessions per week, for 7 weeks (for a total of 35 sessions). The 35 one-hour sessions are aimed at provoking long lasting beneficial changes in the circulatory system.

How effective is it?

EECP now appears to be quite effective in treating chronic stable angina. A randomized trial with EECP, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiologyin 1999, showed that EECP significantly improved both the symptoms of angina (a subjective measurement) and exercise tolerance (a more objective measurement) in patients with coronary artery disease. EECP also significantly improved “quality of life” measures, as compared to placebo therapy.

More recent data show that this improvement in symptoms following a course of EECP seems to persist for up to five years.

Furthermore, there is also preliminary data suggesting that EECP may be useful for treating unstable angina, as adjunctive therapy after revascularization (i.e., with angioplasty, stent, and/or bypass surgery), and even as first-line (instead of last resort) therapy for more routine forms of angina. (Read about EECP as early therapy for angina here.)

Finally, clinical trials have suggested that EECP may be useful in improving symptoms in patients with heart failure. Read about EECP for heart failure here.

How EECP works, and who it may help

Who is likely to benefit from EECP?

Based on what is already known, EECP should be considered in anybody who still has angina despite maximal medical therapy and prior revascularization. No cardiologist could argue logically against this. And, frankly, if a patient insisted on trying EECP prior to agreeing to purely elective revascularization for chronic stable angina, the cardiologist might not like it, but would be hard pressed to give anything beyond a purely emotional reason as to why this should not be tried.

Why does EECP work?

The mechanism for the sustained benefits seen with EECP still amount to speculation. Everyone can agree that there are good reasons for EECP (just as for IACP) to benefit the heart while the therapy is actually taking place. But as to why the benefit of EECP persists even after the therapy is finished, no one can say for sure.

There are preliminary data suggesting that EECP can help induce the formation of collateral vessels in the coronary artery tree, by stimulating the release of nitric oxide and other growth factors in within the coronary arteries.

There is also evidence that EECP may act as a form of “passive” exercise, leading to the same sorts of persistent beneficial changes in the autonomic nervous system that are seen with real exercise.

Can EECP be harmful?

EECP can be somewhat uncomfortable (it is said to be more difficult to watch – what with the patient being noticeably jostled due to the milking action of the inflatable leg cuffs – than it is to actually have it done), but is not painful. In fact, it is apparently very well tolerated by the large majority of patients.

But not everyone can have it. People probably should not have EECP if they have certain types of valvular heart disease (especially aortic insufficiency), or if they have had a recent cardiac catheterization, an irregular heart rhythm, severe hypertension, significant blockages in the leg arteries, or a history of deep venous thrombosis (blood clots in the legs). For anyone else, however, the procedure appears to be quite safe.

Why cardiologists don't like it - and what you should do about it

Despite its increasingly apparent potential usefulness, EECP is hardly taking the cardiology world by storm. In fact, it seems that for most cardiologists EECP is not even on the list of potential treatments for coronary artery disease. Why is that?

There are several possible reasons. Let us dispense with the most obvious first, namely, that EECP doesn’t pay well. A series of 35 treatments costs $5000 to $6000 dollars. That’s not chicken feed, but keep in mind that we’re talking about 35 hours of therapy over 7 weeks, which involves not only the doctor’s time but also the time of office staff, nursing personnel, etc., etc. Still not a terrible return, but when you consider that a cardiologist can often bill that much by spending a morning in the cath lab, well - - -.

Then there’s the fact that EECP remains somewhat intellectually unsatisfying.

To your average cardiologist, there’s no reason at all that anyone should have thought it would work in the first place – that temporarily providing counterpulsation would have lasting effects. And the fact that it apparently does work is merely blind luck, and leaves investigators scrambling ridiculously to explain why it does. This is a less than satisfying way to advance science.

In addition, to most cardiologists, EECP is logistically difficult. To accommodate patients for EECP, they would not only have to purchase expensive equipment, but also would have to radically change the organization of their offices, their office staff, and their space.

Finally, and most importantly, EECP has nothing in common with what cardiologists do. Cardiologists study and treat the heart, for goodness sake. They stress it, image it, measure it, pace it, shock it, stent it, ablate it, revascularize it, and bathe it in drugs. What they do takes years of specialized training and expertise, millions of dollars of high-tech equipment, and tremendous manual dexterity, and it brings them significant prestige, even within the medical community.

Now they’re supposed to drop all that? In order to attach fancy balloons to peoples’ legs, throw a switch, watch them bounce around for an hour, then say, “See you tomorrow?” That’s not cardiology. That’s glorified physical therapy.

This, in DrRich’s estimation, is the real reason the average cardiologist is completely ignoring EECP, as if it doesn’t even exist. They simply can’t believe anyone really expects them to do this.

In any case, you may need to raise your cardiologist’s consciousness. If you have coronary artery disease that has proved difficult to treat, then you need to bring EECP up yourself.

Once enough patients show themselves to be aware of this new therapy and to be expecting it, suddenly EECP will no longer be beneath cardiologists, and they’ll eagerly find a way to incorporate it into their practices.

How can you receive EECP?

If you are a candidate for EECP and wish to pursue it, start with your doctor. If your doctor discourages you from pursuing EECP, make sure he/she gives you a good reason for discouraging it. Good reasons would include: you don’t have the sort of coronary artery disease or angina that would benefit from EECP; your coronary artery disease is of the type that requires revascularization; or you have one of the contraindications (listed above) for having EECP. (Good reasons would not include: it’s unproven; it doesn’t work; it’s voodoo; or I’ve never heard of it.)

There are fewer than 200 places today performing EECP, though the number is growing rapidly. If your doctor can’t think of a place to refer you for EECP, go online. The best place to start online would be EECP.com. This is a website run by Vasomedical, Inc., the company that makes the equipment for EECP, so it is not unbiased. But it does offer an excellent means of finding a place where you can get EECP in your area.

Your insurance carrier should cover EECP, though these fine humanitarians might well deny coverage initially. Medicare has approved EECP for reimbursement, and once Medicare approves a new treatment, insurance companies normally fall in line quite quickly. In the case of EECP, however, many insurance companies are still balking at paying, perhaps because their cardiology consultants are telling them it’s not really a serious therapy. Don’t let this discourage you. If you are turned down for reimbursement, appeal the decision. Most insurance companies count on patients failing to appeal (which is why they so frequently deny therapy that is obviously needed), and with Medicare supporting your contention that EECP ought to be covered, odds are that if you appeal you’ll win.

(From DrRich's article about EECP at About.com)

What is EECP?

EECP is a mechanical procedure in which long inflatable cuffs (like blood pressure cuffs) are wrapped around both of the patient’s legs. While the patient lies on a bed, the leg cuffs are inflated and deflated with each heartbeat. This is accomplished by means of a computer, which triggers off the patient’s ECG so that the cuffs deflate just as each heartbeat begins, and inflate just as each heartbeat ends.

When the cuffs inflate they do so in a sequential fashion, so that the blood in the legs is “milked” upwards, toward the heart.

EECP has two potentially beneficial actions on the heart. First, the milking action of the leg cuffs increases the blood flow to the coronary arteries. (The coronary arteries, unlike other arteries in the body, receive their blood flow after each heartbeat instead of during each heartbeat. EECP, effectively, “pumps” blood into the coronary arteries.) Second, by its deflating action just as the heart begins to beat, EECP creates something like a sudden vacuum in the arteries, which reduces the work of the heart muscle in pumping blood into the arteries. Both of these actions have long been known to reduce cardiac ischemia (the lack of oxygen to the heart muscle) in patients with coronary artery disease. Indeed, an invasive procedure that does the same thing, intra-aortic counterpulsation (IACP, in which a balloon-tipped catheter is positioned in the aorta, which then inflates and deflates in time with the heartbeat), has been in widespread use in intensive care units for decades, and its effectiveness in stabilizing extremely unstable patients is well known.

While a primitive form of external counterpulsation has also been around for a long time, it has not been very effective until recently. Thanks to new computer technology that allows the perfect timing of the inflation and deflation of the cuffs, and produces the milking action, modern EECP has been greatly enhanced.

EECP is administered as a series of outpatient treatments. Patients receive 5 one-hour sessions per week, for 7 weeks (for a total of 35 sessions). The 35 one-hour sessions are aimed at provoking long lasting beneficial changes in the circulatory system.

How effective is it?

EECP now appears to be quite effective in treating chronic stable angina. A randomized trial with EECP, published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiologyin 1999, showed that EECP significantly improved both the symptoms of angina (a subjective measurement) and exercise tolerance (a more objective measurement) in patients with coronary artery disease. EECP also significantly improved “quality of life” measures, as compared to placebo therapy.

More recent data show that this improvement in symptoms following a course of EECP seems to persist for up to five years.

Furthermore, there is also preliminary data suggesting that EECP may be useful for treating unstable angina, as adjunctive therapy after revascularization (i.e., with angioplasty, stent, and/or bypass surgery), and even as first-line (instead of last resort) therapy for more routine forms of angina. (Read about EECP as early therapy for angina here.)

Finally, clinical trials have suggested that EECP may be useful in improving symptoms in patients with heart failure. Read about EECP for heart failure here.

How EECP works, and who it may help

Who is likely to benefit from EECP?

Based on what is already known, EECP should be considered in anybody who still has angina despite maximal medical therapy and prior revascularization. No cardiologist could argue logically against this. And, frankly, if a patient insisted on trying EECP prior to agreeing to purely elective revascularization for chronic stable angina, the cardiologist might not like it, but would be hard pressed to give anything beyond a purely emotional reason as to why this should not be tried.

Why does EECP work?

The mechanism for the sustained benefits seen with EECP still amount to speculation. Everyone can agree that there are good reasons for EECP (just as for IACP) to benefit the heart while the therapy is actually taking place. But as to why the benefit of EECP persists even after the therapy is finished, no one can say for sure.

There are preliminary data suggesting that EECP can help induce the formation of collateral vessels in the coronary artery tree, by stimulating the release of nitric oxide and other growth factors in within the coronary arteries.

There is also evidence that EECP may act as a form of “passive” exercise, leading to the same sorts of persistent beneficial changes in the autonomic nervous system that are seen with real exercise.

Can EECP be harmful?

EECP can be somewhat uncomfortable (it is said to be more difficult to watch – what with the patient being noticeably jostled due to the milking action of the inflatable leg cuffs – than it is to actually have it done), but is not painful. In fact, it is apparently very well tolerated by the large majority of patients.

But not everyone can have it. People probably should not have EECP if they have certain types of valvular heart disease (especially aortic insufficiency), or if they have had a recent cardiac catheterization, an irregular heart rhythm, severe hypertension, significant blockages in the leg arteries, or a history of deep venous thrombosis (blood clots in the legs). For anyone else, however, the procedure appears to be quite safe.

Why cardiologists don't like it - and what you should do about it

Despite its increasingly apparent potential usefulness, EECP is hardly taking the cardiology world by storm. In fact, it seems that for most cardiologists EECP is not even on the list of potential treatments for coronary artery disease. Why is that?

There are several possible reasons. Let us dispense with the most obvious first, namely, that EECP doesn’t pay well. A series of 35 treatments costs $5000 to $6000 dollars. That’s not chicken feed, but keep in mind that we’re talking about 35 hours of therapy over 7 weeks, which involves not only the doctor’s time but also the time of office staff, nursing personnel, etc., etc. Still not a terrible return, but when you consider that a cardiologist can often bill that much by spending a morning in the cath lab, well - - -.

Then there’s the fact that EECP remains somewhat intellectually unsatisfying.

To your average cardiologist, there’s no reason at all that anyone should have thought it would work in the first place – that temporarily providing counterpulsation would have lasting effects. And the fact that it apparently does work is merely blind luck, and leaves investigators scrambling ridiculously to explain why it does. This is a less than satisfying way to advance science.

In addition, to most cardiologists, EECP is logistically difficult. To accommodate patients for EECP, they would not only have to purchase expensive equipment, but also would have to radically change the organization of their offices, their office staff, and their space.

Finally, and most importantly, EECP has nothing in common with what cardiologists do. Cardiologists study and treat the heart, for goodness sake. They stress it, image it, measure it, pace it, shock it, stent it, ablate it, revascularize it, and bathe it in drugs. What they do takes years of specialized training and expertise, millions of dollars of high-tech equipment, and tremendous manual dexterity, and it brings them significant prestige, even within the medical community.

Now they’re supposed to drop all that? In order to attach fancy balloons to peoples’ legs, throw a switch, watch them bounce around for an hour, then say, “See you tomorrow?” That’s not cardiology. That’s glorified physical therapy.

This, in DrRich’s estimation, is the real reason the average cardiologist is completely ignoring EECP, as if it doesn’t even exist. They simply can’t believe anyone really expects them to do this.

In any case, you may need to raise your cardiologist’s consciousness. If you have coronary artery disease that has proved difficult to treat, then you need to bring EECP up yourself.

Once enough patients show themselves to be aware of this new therapy and to be expecting it, suddenly EECP will no longer be beneath cardiologists, and they’ll eagerly find a way to incorporate it into their practices.

How can you receive EECP?

If you are a candidate for EECP and wish to pursue it, start with your doctor. If your doctor discourages you from pursuing EECP, make sure he/she gives you a good reason for discouraging it. Good reasons would include: you don’t have the sort of coronary artery disease or angina that would benefit from EECP; your coronary artery disease is of the type that requires revascularization; or you have one of the contraindications (listed above) for having EECP. (Good reasons would not include: it’s unproven; it doesn’t work; it’s voodoo; or I’ve never heard of it.)

There are fewer than 200 places today performing EECP, though the number is growing rapidly. If your doctor can’t think of a place to refer you for EECP, go online. The best place to start online would be EECP.com. This is a website run by Vasomedical, Inc., the company that makes the equipment for EECP, so it is not unbiased. But it does offer an excellent means of finding a place where you can get EECP in your area.

Your insurance carrier should cover EECP, though these fine humanitarians might well deny coverage initially. Medicare has approved EECP for reimbursement, and once Medicare approves a new treatment, insurance companies normally fall in line quite quickly. In the case of EECP, however, many insurance companies are still balking at paying, perhaps because their cardiology consultants are telling them it’s not really a serious therapy. Don’t let this discourage you. If you are turned down for reimbursement, appeal the decision. Most insurance companies count on patients failing to appeal (which is why they so frequently deny therapy that is obviously needed), and with Medicare supporting your contention that EECP ought to be covered, odds are that if you appeal you’ll win.

(From DrRich's article about EECP at About.com)

Saturday, March 10, 2007

Stop Working? No Way!

Anyone who has been following my blog knows I decided to take an alternative treatment to the quintuple bypass surgery my Indiana invasive cardiologist wanted me to have in 2004. My angina disappeared for two-and-a-half years on medication alone. In November 2006, the angina reurned. It is "stable" angina, occuring on exertion, readily relieved with NTG sublingually. It seems to occur mostly when my blood pressure show a diastolic reading of over 80 and a systolic of over 128.

My cardiologist, who is not a true noninvasive practitioner, has cooperated with my desire to continue medical treatment rather than undergo a bypass. We are fiddling with my meds and I am watching my diet better.

There is some consternation that I have opted to contineu working in an isolated part of the world, Nigeria, however, I choose to keep working because it is what I enjoy doing the most. There is another person I know of who has many medical, especially cardiac, problems and he too has decided to keep working. I can't say, I want to emulate him or that he is my hero, because I am vehemently opposed to his politics, however, I do give him credit for being his own man.

See his story here.

My cardiologist, who is not a true noninvasive practitioner, has cooperated with my desire to continue medical treatment rather than undergo a bypass. We are fiddling with my meds and I am watching my diet better.

There is some consternation that I have opted to contineu working in an isolated part of the world, Nigeria, however, I choose to keep working because it is what I enjoy doing the most. There is another person I know of who has many medical, especially cardiac, problems and he too has decided to keep working. I can't say, I want to emulate him or that he is my hero, because I am vehemently opposed to his politics, however, I do give him credit for being his own man.

See his story here.

Saturday, March 03, 2007

Viagra -- Better Than Nitroglycerin?

Erectile dysfunction drugs may be better than nitroglycerin in protecting the heart from damage before and after a severe heart attack, Virginia Commonwealth University researchers report today.

During a heart attack, the heart is deprived of oxygen, which can result in significant damage to heart muscle and tissue. After the attack, most patients require treatment to reduce and repair the damage and improve their chances of survival. With the exception of early reperfusion, there are no available therapies that are truly effective in protecting or repairing such damage clinically.

Rakesh C. Kukreja, Ph.D., professor of medicine and Eric Lipman Chair of Cardiology at VCU, and colleagues compared nitroglycerin with two erectile dysfunction drugs -- Viagra®, generically known as sildenafil, and Levitra®, generically known as vardenafil -- to determine the effectiveness of each for heart protection following a heart attack. Nitroglycerin is a drug used to treat angina, or chest pain. It is a vasodilator and opens blood vessels in order to improve the flow of blood to a patient’s heart.The research team reported that in an animal model, sildenafil and vardenafil reduce damage in the heart muscle when given after a severe heart attack. In contrast, nitroglycerin failed to reduce the damage in the heart when administered under similar conditions. The findings were published in the February issue of the Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, the official publication of the International Society for Heart Research.

“Erectile dysfunction drugs can prevent damage in the heart not only when given before a heart attack, as we discovered previously, but also lessen the injury after the heart attack,” said Kukreja, who is the lead author of the study.

According to Kukreja, the protective effects on the heart produced by these erectile dysfunction drugs may be potentially useful as adjunct therapy in patients undergoing elective procedures, including coronary artery bypass graft, coronary angioplasty or heart transplantation. In addition, he said another potential application could be to prevent the multiple organ damage that occurs following cardiac arrest, resuscitation or shock.

“Preserving heart function is critical to optimal cardiac outcomes,” said George W. Vetrovec, M.D., chair of cardiology at the VCU Pauley Heart Center. “These agents have significant potential to enhance patient outcomes, particularly in high risk circumstances, such as acute heart attacks.”

For several years, Kukreja and his colleagues have studied a class of erectile dysfunction drugs known as phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors as part of ongoing research into heart protection. The team first investigated sildenafil, and then vardenafil, and found that both compounds were protective when given before a heart attack under experimental conditions.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Pfizer Inc., and Bayer Healthcare AG.

The Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology is published by Elsevier Publishing.

Always consult with your health care provider before changing your medication regimen. Never take ED drugs when you are taking Nitroglycerin.

During a heart attack, the heart is deprived of oxygen, which can result in significant damage to heart muscle and tissue. After the attack, most patients require treatment to reduce and repair the damage and improve their chances of survival. With the exception of early reperfusion, there are no available therapies that are truly effective in protecting or repairing such damage clinically.

Rakesh C. Kukreja, Ph.D., professor of medicine and Eric Lipman Chair of Cardiology at VCU, and colleagues compared nitroglycerin with two erectile dysfunction drugs -- Viagra®, generically known as sildenafil, and Levitra®, generically known as vardenafil -- to determine the effectiveness of each for heart protection following a heart attack. Nitroglycerin is a drug used to treat angina, or chest pain. It is a vasodilator and opens blood vessels in order to improve the flow of blood to a patient’s heart.The research team reported that in an animal model, sildenafil and vardenafil reduce damage in the heart muscle when given after a severe heart attack. In contrast, nitroglycerin failed to reduce the damage in the heart when administered under similar conditions. The findings were published in the February issue of the Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology, the official publication of the International Society for Heart Research.

“Erectile dysfunction drugs can prevent damage in the heart not only when given before a heart attack, as we discovered previously, but also lessen the injury after the heart attack,” said Kukreja, who is the lead author of the study.

According to Kukreja, the protective effects on the heart produced by these erectile dysfunction drugs may be potentially useful as adjunct therapy in patients undergoing elective procedures, including coronary artery bypass graft, coronary angioplasty or heart transplantation. In addition, he said another potential application could be to prevent the multiple organ damage that occurs following cardiac arrest, resuscitation or shock.

“Preserving heart function is critical to optimal cardiac outcomes,” said George W. Vetrovec, M.D., chair of cardiology at the VCU Pauley Heart Center. “These agents have significant potential to enhance patient outcomes, particularly in high risk circumstances, such as acute heart attacks.”

For several years, Kukreja and his colleagues have studied a class of erectile dysfunction drugs known as phosphodiesterase-5 inhibitors as part of ongoing research into heart protection. The team first investigated sildenafil, and then vardenafil, and found that both compounds were protective when given before a heart attack under experimental conditions.

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, Pfizer Inc., and Bayer Healthcare AG.

The Journal of Molecular and Cellular Cardiology is published by Elsevier Publishing.

Always consult with your health care provider before changing your medication regimen. Never take ED drugs when you are taking Nitroglycerin.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)