Thursday, January 25, 2007

Why don't the pharmaceutical companies tout this study?

Risk Factors for Coronary Artery Disease in Patients With Elevated High-Density Lipoprotein Cholesterol

In a January 1, Journal of Cardiology story, it was concluded that patients with high HDL and CAD had a similar or lower prevalence of traditional CAD risk factors compared with patients with normal HDL levels and CAD. In other words, your cholesterol level means squat. Why then hasn't this news been heralded around the globe? I'll tell you why, it is not in the financial interests of the pharmaceutical industry. These modern day medicine show performers would rather have people pay huge prices for something they don't even need, that even may be harmful to them.

People with high cholesterol live longest

People with high cholesterol live the longest. This statement seems so incredible that it takes a long time to clear one´s brainwashed mind to fully understand its importance. Yet the fact that people with high cholesterol live the longest emerges clearly from many scientific papers. Consider the finding of Dr. Harlan Krumholz of the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine at Yale University, who reported in 1994 that old people with low cholesterol died twice as often from a heart attack as did old people with a high cholesterol.1 Supporters of the cholesterol campaign consistently ignore his observation, or consider it as a rare exception, produced by chance among a huge number of studies finding the opposite.

Of course,, you've got to keep in mind, the pharmaceutical companies market their products to the hilt, especially the new ones people think they need. Some of the "statins" cost upwards to 10 dollars per tablet!

Please read (Almost) Everything You Need to Know About Statin Drugs by Maryann Napoli

or read The Cholesterol Myths by the foremost authority on cholesterol, Uffe Ravnskov, MD,PhD

After you have read all about cholesterol, the pros and the cons, check and see who funds most of the positive anti-cholesterol therapy studies. Merk, Eli Lily, Pfizer, and other drug companies.

It's time for the healthcare product consumer to stand up and take charge of his and her own bodies. You cannot trust medical terrorists and mercenaries to work in your best interests. Always get a second opinion if a cardiologist your family physician sent you to says you need a quintuple coronary artery bypass. Never accept a new cholesterol medication simply because your doctor thinks its great -- check it out.

In a January 1, Journal of Cardiology story, it was concluded that patients with high HDL and CAD had a similar or lower prevalence of traditional CAD risk factors compared with patients with normal HDL levels and CAD. In other words, your cholesterol level means squat. Why then hasn't this news been heralded around the globe? I'll tell you why, it is not in the financial interests of the pharmaceutical industry. These modern day medicine show performers would rather have people pay huge prices for something they don't even need, that even may be harmful to them.

People with high cholesterol live longest

People with high cholesterol live the longest. This statement seems so incredible that it takes a long time to clear one´s brainwashed mind to fully understand its importance. Yet the fact that people with high cholesterol live the longest emerges clearly from many scientific papers. Consider the finding of Dr. Harlan Krumholz of the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine at Yale University, who reported in 1994 that old people with low cholesterol died twice as often from a heart attack as did old people with a high cholesterol.1 Supporters of the cholesterol campaign consistently ignore his observation, or consider it as a rare exception, produced by chance among a huge number of studies finding the opposite.

Of course,, you've got to keep in mind, the pharmaceutical companies market their products to the hilt, especially the new ones people think they need. Some of the "statins" cost upwards to 10 dollars per tablet!

Please read (Almost) Everything You Need to Know About Statin Drugs by Maryann Napoli

or read The Cholesterol Myths by the foremost authority on cholesterol, Uffe Ravnskov, MD,PhD

After you have read all about cholesterol, the pros and the cons, check and see who funds most of the positive anti-cholesterol therapy studies. Merk, Eli Lily, Pfizer, and other drug companies.

It's time for the healthcare product consumer to stand up and take charge of his and her own bodies. You cannot trust medical terrorists and mercenaries to work in your best interests. Always get a second opinion if a cardiologist your family physician sent you to says you need a quintuple coronary artery bypass. Never accept a new cholesterol medication simply because your doctor thinks its great -- check it out.

Friday, January 19, 2007

Uh Oh... we'd better stop doing that!

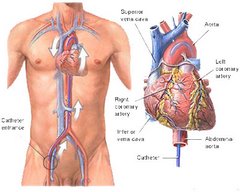

It's not nice to fool Mother Nature -- It seemed like a good idea, but combining a carotid endarterectomy with a coronary artery bypass graft increased the risk of postoperative stroke and death by nearly 40% over CABG alone, investigators reported.

In a review of records on patients nationwide who underwent CABG with or without carotid endarterectomy, the odds ratio for a combined endpoint of postoperative stroke or death was 2.25 for patients who underwent both procedures, reported Richard M. Dubinsky, M.D., M.P.H., and Sue Min Lai, Ph.D., M.B.A., of the University of Kansas Medical Center.

After correction for co-morbidities, the odds ratio was reduced to a smaller but still significant 1.38 compared with patients who underwent CABG only, they wrote in the Jan. 15 issue of Neurology.

Their findings suggest that theoretical benefit of combining the surgeries may not outweigh the increased risks.

"The underlying rationales for combined carotid endarterectomy-CABG are to protect the carotid circulation from artery-to-artery embolic stroke during CABG and to lessen the risk by having just one operation, albeit longer, and one exposure to anesthesia," the authors wrote.

"Although there is an increased likelihood of carotid artery disease in those with coronary artery disease, the risk of asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis is low enough that perioperative mortality can be greater than the benefit of reduced risk of stroke compared with medication alone."

The investigators conducted a retrospective study of records from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, a database that provides yearly admission and discharge data from nearly 1,000 hospitals.

They extracted data on community-wide mortality and morbidity rates in patients undergoing combined carotid-endarterectomy-CABG in the United States from 1993 through 2002.

The cohort included 657,877 patients ranging from 32 to 89 years old, 178,959 of whom underwent endarterectomy alone, 471,881 who underwent CABG alone, and 7,037 who underwent both procedures. Of the combined surgery group, 1,203 were known to have undergone the procedures on the same day; the spacing of procedures in the remaining 5,807 was unknown.

The investigators calculated the odds ratio for the combined outcomes of postoperative stroke or death for same-day endarterectomy-CABG to be 2.16 (95% confidence interval 1.78 to 2.62, P<0.0001) compared with CABG alone, and for those patients in whom the spacing of the procedures was unknown the odds ratio was 2.28 (95% CI 2.08 to 2.48, P<0.0001). For all combined procedures the odds ratio was 2.25 (95% CI 2.08 to 2.44, P<0.0001).

There were no changes over time in the rate of postoperative stroke or death in the combined surgery groups, the authors noted.

In a logistic regression model of those older than 65, procedures performed in urban non-teaching hospitals, and co-morbidities (Charlson index score > 1) were also associated with increased risk for in-hospital death and postoperative stroke, with female sex being the only factor associated with lower in-hospital mortality for people undergoing both procedures.

"The logistic regression models confirmed that for combined carotid endarterectomy-CABG, the higher risk persisted even after controlling for all risk factors and remained unchanged when individual comorbidities (rather than the co-morbidity index) were analyzed," the investigators wrote.

The adjusted odds ratio for the combined endpoint of postoperative stroke or death was 1.38 (95% CI 1.27-1.50, P<0.0001).

The authors noted that the increased risk seen with the combined procedures might be attributable to residual confounders, such as previous stroke or the degree of carotid artery stenosis.

They also acknowledged that the administrative data they relied on could include diagnostic coding errors and omissions of some co-morbidities. Their analysis could not account for the degree of carotid stenosis, extent of previous strokes, use of pre-operative medical therapies, or physician experience.

"The frequency of combined carotid endarterectomy-CABG has increased, but the reported case series are inadequate to conclude whether there is a benefit to combining the procedures," Dr. Dubinsky and Dr. Lai wrote. "A randomized controlled clinical trial, stratified for the degree of carotid stenosis and for previous stroke, with a follow-up of at least one year, is clearly needed to determine the benefit, if any, of combined carotid endarterectomy-CABG in patients with carotid and coronary atherosclerosis."

This just goes to show you that surgical procedures should be approved by an entity like the FDA before being introduced into use on the general population. How would you like to be or have had one of your loved ones be one of that 40%?

At the very least, cardio-thoracic surgeons should:

1. tell the patient studies show when the CABG and carotid endarterectomy are performed together, there is about a 40% higher risk of stroke or death after surgery than for CABG alone.

2. point out that not all co-morbidities could be determined in this study and a randomize, controlled trial would be necessary to determine the benefits of lack of benefit of this procedure.

In a review of records on patients nationwide who underwent CABG with or without carotid endarterectomy, the odds ratio for a combined endpoint of postoperative stroke or death was 2.25 for patients who underwent both procedures, reported Richard M. Dubinsky, M.D., M.P.H., and Sue Min Lai, Ph.D., M.B.A., of the University of Kansas Medical Center.

After correction for co-morbidities, the odds ratio was reduced to a smaller but still significant 1.38 compared with patients who underwent CABG only, they wrote in the Jan. 15 issue of Neurology.

Their findings suggest that theoretical benefit of combining the surgeries may not outweigh the increased risks.

"The underlying rationales for combined carotid endarterectomy-CABG are to protect the carotid circulation from artery-to-artery embolic stroke during CABG and to lessen the risk by having just one operation, albeit longer, and one exposure to anesthesia," the authors wrote.

"Although there is an increased likelihood of carotid artery disease in those with coronary artery disease, the risk of asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis is low enough that perioperative mortality can be greater than the benefit of reduced risk of stroke compared with medication alone."

The investigators conducted a retrospective study of records from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample, a database that provides yearly admission and discharge data from nearly 1,000 hospitals.

They extracted data on community-wide mortality and morbidity rates in patients undergoing combined carotid-endarterectomy-CABG in the United States from 1993 through 2002.

The cohort included 657,877 patients ranging from 32 to 89 years old, 178,959 of whom underwent endarterectomy alone, 471,881 who underwent CABG alone, and 7,037 who underwent both procedures. Of the combined surgery group, 1,203 were known to have undergone the procedures on the same day; the spacing of procedures in the remaining 5,807 was unknown.

The investigators calculated the odds ratio for the combined outcomes of postoperative stroke or death for same-day endarterectomy-CABG to be 2.16 (95% confidence interval 1.78 to 2.62, P<0.0001) compared with CABG alone, and for those patients in whom the spacing of the procedures was unknown the odds ratio was 2.28 (95% CI 2.08 to 2.48, P<0.0001). For all combined procedures the odds ratio was 2.25 (95% CI 2.08 to 2.44, P<0.0001).

There were no changes over time in the rate of postoperative stroke or death in the combined surgery groups, the authors noted.

In a logistic regression model of those older than 65, procedures performed in urban non-teaching hospitals, and co-morbidities (Charlson index score > 1) were also associated with increased risk for in-hospital death and postoperative stroke, with female sex being the only factor associated with lower in-hospital mortality for people undergoing both procedures.

"The logistic regression models confirmed that for combined carotid endarterectomy-CABG, the higher risk persisted even after controlling for all risk factors and remained unchanged when individual comorbidities (rather than the co-morbidity index) were analyzed," the investigators wrote.

The adjusted odds ratio for the combined endpoint of postoperative stroke or death was 1.38 (95% CI 1.27-1.50, P<0.0001).

The authors noted that the increased risk seen with the combined procedures might be attributable to residual confounders, such as previous stroke or the degree of carotid artery stenosis.

They also acknowledged that the administrative data they relied on could include diagnostic coding errors and omissions of some co-morbidities. Their analysis could not account for the degree of carotid stenosis, extent of previous strokes, use of pre-operative medical therapies, or physician experience.

"The frequency of combined carotid endarterectomy-CABG has increased, but the reported case series are inadequate to conclude whether there is a benefit to combining the procedures," Dr. Dubinsky and Dr. Lai wrote. "A randomized controlled clinical trial, stratified for the degree of carotid stenosis and for previous stroke, with a follow-up of at least one year, is clearly needed to determine the benefit, if any, of combined carotid endarterectomy-CABG in patients with carotid and coronary atherosclerosis."

This just goes to show you that surgical procedures should be approved by an entity like the FDA before being introduced into use on the general population. How would you like to be or have had one of your loved ones be one of that 40%?

At the very least, cardio-thoracic surgeons should:

1. tell the patient studies show when the CABG and carotid endarterectomy are performed together, there is about a 40% higher risk of stroke or death after surgery than for CABG alone.

2. point out that not all co-morbidities could be determined in this study and a randomize, controlled trial would be necessary to determine the benefits of lack of benefit of this procedure.

Saturday, January 13, 2007

Low "Good" Cholesterol Level Protects Parkinson's Patients from Heart Attacks??

People with low levels of LDL cholesterol are more likely to have Parkinson’s disease than people with high LDL levels, according to University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill researchers.LDL stands for low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; low levels of LDL cholesterol are considered an indicator of good cardiovascular health. Earlier studies have found intriguing correlations between Parkinson’s disease, heart attacks, stroke and smoking.

“People with Parkinson’s disease have a lower occurrence of heart attack and stroke than people who do not have the disease,” said Dr. Xuemei Huang, medical director of the Movement Disorder Clinic at UNC Hospitals and an assistant professor of neurology in the UNC School of Medicine. “Parkinson’s patients are also more likely to carry the gene APOE-2, which is linked with lower LDL cholesterol.” And for more than a decade, researchers have known that smoking, which increases a person’s risk for cardiovascular disease, is also associated with a decreased risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Well, I have a pretty severe case of CAD, I was told in 2004 I needed a quintuple coronary artery bypass, but I opted for treatment with medication. I am doing very well on medication and am told by my doctors that my heart is in great shape. I guess I have my Parkinson's deisease to thank for that. I suppose I could say the PD is a blessing in disguise.

These findings led Huang to examine whether higher LDL cholesterol might be associated with a decreased occurrence for Parkinson’s disease, and vice versa. “If my hypothesis was correct,” she said, “lower LDL-C, something that is linked to healthy hearts, would be associated with a higher occurrence of Parkinson’s.” The results of Huang’s study, published online Dec. 18 by the journal Movement Disorders, confirmed her hypothesis. “We found that lower LDL concentrations were indeed associated with a higher occurrence of Parkinson’s disease,” Huang said. Participants with lower LDL levels (less than 114 milligrams per deciliter) had a 3.5-fold higher occurrence of Parkinson’s than the participants with higher LDL levels (more than 138 milligrams per deciliter).

Huang cautioned that people should not change their eating habits, nor their use of statins and other cholesterol-lowering drugs, because of the results. The study was based on relatively small numbers of cases and controls, and the results are too preliminary, she said. Further large prospective studies are needed, Huang added.

“Parkinson’s is a disease full of paradoxes,” Huang said. “We’ve known for years that smoking reduces the risk of developing Parkinson’s. More than 40 studies have documented that fact. But we don’t advise people to smoke because of the other more serious health risks,” she said.

Huang and her colleagues recruited 124 Parkinson’s patients who were treated at the UNC Movement Disorder Clinic between July 2002 and November 2004 to take part in the study. Another 112 people, all spouses of patients treated in the clinic, were recruited as the control group. Fasting cholesterol profiles were obtained from each participant. The researchers also recorded information on each participant’s gender, age, smoking habits and use of cholesterol-lowering drugs.

Huang notes that the study also found participants with Parkinson’s were much less likely to take cholesterol-lowering drugs than participants in the control group. This, combined with the findings about LDL cholesterol, suggests two questions for additional study, Huang said.

“One is whether lower cholesterol predates the onset of Parkinson’s. Number two, what is the role of statins in that? In other words, does taking cholesterol-lowering drugs somehow protect against Parkinson’s? We need to address these questions,” she said.

“People with Parkinson’s disease have a lower occurrence of heart attack and stroke than people who do not have the disease,” said Dr. Xuemei Huang, medical director of the Movement Disorder Clinic at UNC Hospitals and an assistant professor of neurology in the UNC School of Medicine. “Parkinson’s patients are also more likely to carry the gene APOE-2, which is linked with lower LDL cholesterol.” And for more than a decade, researchers have known that smoking, which increases a person’s risk for cardiovascular disease, is also associated with a decreased risk of Parkinson’s disease.

Well, I have a pretty severe case of CAD, I was told in 2004 I needed a quintuple coronary artery bypass, but I opted for treatment with medication. I am doing very well on medication and am told by my doctors that my heart is in great shape. I guess I have my Parkinson's deisease to thank for that. I suppose I could say the PD is a blessing in disguise.

These findings led Huang to examine whether higher LDL cholesterol might be associated with a decreased occurrence for Parkinson’s disease, and vice versa. “If my hypothesis was correct,” she said, “lower LDL-C, something that is linked to healthy hearts, would be associated with a higher occurrence of Parkinson’s.” The results of Huang’s study, published online Dec. 18 by the journal Movement Disorders, confirmed her hypothesis. “We found that lower LDL concentrations were indeed associated with a higher occurrence of Parkinson’s disease,” Huang said. Participants with lower LDL levels (less than 114 milligrams per deciliter) had a 3.5-fold higher occurrence of Parkinson’s than the participants with higher LDL levels (more than 138 milligrams per deciliter).

Huang cautioned that people should not change their eating habits, nor their use of statins and other cholesterol-lowering drugs, because of the results. The study was based on relatively small numbers of cases and controls, and the results are too preliminary, she said. Further large prospective studies are needed, Huang added.

“Parkinson’s is a disease full of paradoxes,” Huang said. “We’ve known for years that smoking reduces the risk of developing Parkinson’s. More than 40 studies have documented that fact. But we don’t advise people to smoke because of the other more serious health risks,” she said.

Huang and her colleagues recruited 124 Parkinson’s patients who were treated at the UNC Movement Disorder Clinic between July 2002 and November 2004 to take part in the study. Another 112 people, all spouses of patients treated in the clinic, were recruited as the control group. Fasting cholesterol profiles were obtained from each participant. The researchers also recorded information on each participant’s gender, age, smoking habits and use of cholesterol-lowering drugs.

Huang notes that the study also found participants with Parkinson’s were much less likely to take cholesterol-lowering drugs than participants in the control group. This, combined with the findings about LDL cholesterol, suggests two questions for additional study, Huang said.

“One is whether lower cholesterol predates the onset of Parkinson’s. Number two, what is the role of statins in that? In other words, does taking cholesterol-lowering drugs somehow protect against Parkinson’s? We need to address these questions,” she said.

Friday, January 12, 2007

Dr. Andrew Chung, MD, PhD

Dr. Andrew B. Chung, MD, PhD, an invasive/noninterventional cardiologist practicing in Georgia, has invited all former patients of the late Dr. Wayne to the sci.med.cardiology usenet newsgroup to receive his public comments about our experiences. Dr. Chung does a great deal of patient education via email and the Internet and is a good resource for any lay person about health related topics. The URL of his cardiology newsgroup is

http://groups.google.com/group/sci.med.cardiology/msg/d114c7fea319e0fb?

http://groups.google.com/group/sci.med.cardiology/msg/d114c7fea319e0fb?

Tuesday, January 09, 2007

Replacing Dr. Wayne

Today was my appointment with Dr. Stephen DeVries, a noninvasive cardiologist who practices in the University of Illinois Medical Center in Chicago. I know I promised several of Dr. Wayne's patients that I would provide them with a critique of my experience and I have been pondering what I should write. Let me tell you about my visit to the Illinois Medical Center Heart Center.

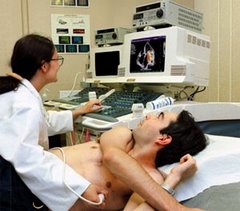

I was escorted from the waiting room by a very friendly and efficient RN. She obtained my weight and vital signs, took a history and asked of my current symptoms and had me list all of the medications, both cardiac related and otherwise. The only thing she seemed surprised at was my BP reading - 98/52. Then I was taken to another room by an EKG technician. She took about ten minutes setting me up and fiddling with the leads until all interference was gone and then she took the EKG.

Dr. DeVries entered the exam room within a few minutes after I had come back from the EKG. A thin, unopposing, affable man with a winning smile and great bedside manner, I immediately felt comfortable with him. Once we got the small talk out of the way, I told Dr. DeVries about the loss of the best cardiologist I ever had and told him frankly that this visit was an interview in search of a suitable replacement. Whether or not I chose him, depended on how he answered my questions.

He replied by saying he respected the patient's right to take charge of his own medical treatment. Likening himself to a presidential advisor, DeVries said, "The president gets advice from different advisors about which country to go to war with, but the final decsion lays with the president." He would give me advice and would give me all the facts so I could make a rational decision.

I explained to Dr. DeVries that I had been angina-free from May 2004 to November 2006, by taking Dr. Wayne's medical regimen. But in November, while running through Charles De Gaulle airport in Paris, I felt a twinge of angina. Since then, these twinges have repeated themselves several times a day, during exetion or fairly severe stress.

Dr. DeVries, although a noninvasive cardiologist, said he felt I needed a new stress test and nuclear images by cardiography during the test. I told him I no doubt would fail, then he replied, "Then I would recommend an angiogram and if necessary, possible stents."

Dr. Wayne had warned me that the medicine probably wouldn't work for ever and I may need a CABG some time in the future. He also had told me on many occasions, that angiograms were useless tools, so the fact that Dr. DeVries wanted me to have one sent a red flag up. I asked why a 64 slice CT wouldn't be acceptable and he responded, "When we do an angiogram, we can put stents in or do a baloon angioplasty." Again, not eh most encouraging response.

He asked about my cholesterol level and I said I had no idea what the numbers were and that Dr. Wayne strongly objected to me being prescribed Lipitor by my neurologist. I told him I wasn't worried about the cholesterol levels and he still wants me to get fasting lab work to check my levels.

I like Dr. DeVries and until I can find a cardiologist who seems to be schooled in the techniques and philosophy of Dr. Wayne, will probably continue to see him. I will do the blood work and the stress test and cardiography but I will, under no circumstances allow stents or angioplasty.

I don't know if I will get a CABG or not. Dr. DeVries prescribed Imdur 60mg i qd and NTG 1/150 i SL prn chest pain x 3 to be added to the medication regimen I am already on. He also increased my aspirin from 81mg daily to 325mg qd and recommended Nordic Natural EPA Fish Oil pills, 2 with breakfast. Let's see how that does.

I also will see Dr. DeVries in February, after I return from my work in Africa. So while I am going to start seeing Dr. DeVries for the time being, I cannot recommend him as a replacement for Dr. Wayne. You may want to check out Dr. Thomas A Preston, MD, Professor of Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine and Chief of Cardiology at Pacific Medical Center, Seattle, Washington. Scroll down to his guest editorial.

Also, check my Cholesterol Conspiracy Links. You will find them very enlightening.

I was escorted from the waiting room by a very friendly and efficient RN. She obtained my weight and vital signs, took a history and asked of my current symptoms and had me list all of the medications, both cardiac related and otherwise. The only thing she seemed surprised at was my BP reading - 98/52. Then I was taken to another room by an EKG technician. She took about ten minutes setting me up and fiddling with the leads until all interference was gone and then she took the EKG.

Dr. DeVries entered the exam room within a few minutes after I had come back from the EKG. A thin, unopposing, affable man with a winning smile and great bedside manner, I immediately felt comfortable with him. Once we got the small talk out of the way, I told Dr. DeVries about the loss of the best cardiologist I ever had and told him frankly that this visit was an interview in search of a suitable replacement. Whether or not I chose him, depended on how he answered my questions.

He replied by saying he respected the patient's right to take charge of his own medical treatment. Likening himself to a presidential advisor, DeVries said, "The president gets advice from different advisors about which country to go to war with, but the final decsion lays with the president." He would give me advice and would give me all the facts so I could make a rational decision.

I explained to Dr. DeVries that I had been angina-free from May 2004 to November 2006, by taking Dr. Wayne's medical regimen. But in November, while running through Charles De Gaulle airport in Paris, I felt a twinge of angina. Since then, these twinges have repeated themselves several times a day, during exetion or fairly severe stress.

Dr. DeVries, although a noninvasive cardiologist, said he felt I needed a new stress test and nuclear images by cardiography during the test. I told him I no doubt would fail, then he replied, "Then I would recommend an angiogram and if necessary, possible stents."

Dr. Wayne had warned me that the medicine probably wouldn't work for ever and I may need a CABG some time in the future. He also had told me on many occasions, that angiograms were useless tools, so the fact that Dr. DeVries wanted me to have one sent a red flag up. I asked why a 64 slice CT wouldn't be acceptable and he responded, "When we do an angiogram, we can put stents in or do a baloon angioplasty." Again, not eh most encouraging response.

He asked about my cholesterol level and I said I had no idea what the numbers were and that Dr. Wayne strongly objected to me being prescribed Lipitor by my neurologist. I told him I wasn't worried about the cholesterol levels and he still wants me to get fasting lab work to check my levels.

I like Dr. DeVries and until I can find a cardiologist who seems to be schooled in the techniques and philosophy of Dr. Wayne, will probably continue to see him. I will do the blood work and the stress test and cardiography but I will, under no circumstances allow stents or angioplasty.

I don't know if I will get a CABG or not. Dr. DeVries prescribed Imdur 60mg i qd and NTG 1/150 i SL prn chest pain x 3 to be added to the medication regimen I am already on. He also increased my aspirin from 81mg daily to 325mg qd and recommended Nordic Natural EPA Fish Oil pills, 2 with breakfast. Let's see how that does.

I also will see Dr. DeVries in February, after I return from my work in Africa. So while I am going to start seeing Dr. DeVries for the time being, I cannot recommend him as a replacement for Dr. Wayne. You may want to check out Dr. Thomas A Preston, MD, Professor of Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine and Chief of Cardiology at Pacific Medical Center, Seattle, Washington. Scroll down to his guest editorial.

Also, check my Cholesterol Conspiracy Links. You will find them very enlightening.

Screening CT-Coronary Angiography: Ready for Prime Time?

The advent of very advanced CAT scan imaging has enabled cardiologists to detect the earliest calcified and non-calcified plaque in coronary arteries. This noninvasive procedure has allowed the early detection of coronary artery disease before patients are stricken with sudden cardiac death and myocardial infarction (heart attack).

Westside Medical Imaging has been a pioneer and leader in the field of coronary imaging and 64 slice CT coronary angiography having performed nearly 4,000 scans to date and with that having an important impact on many lives. The use of 64 slice cardiac CT as a screening examination has been evaluated by Norman Lepor MD in a recent publication in the medical journal, Reviews in Cardiovascular Medicine.

Dr. Lepor is an Associate Clinical Professor of Medicine at the Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA and the co-director of Cardiovascular Imaging at Westside Medical Imaging. In this pivotal publication, Dr. Lepor describes the ability of this important technology to detect heart disease in the presymptomatic phase. In addition, he discusses the shortcoming of the current method of risk assessment using risk factor analysis which often underestimates the risk certain populations. Dr. Lepor describes in detail the risk and benefits of this approach.

He recommends that any person with one or more of the following heart attack risk factors including diabetes, smoker (past or current), high blood pressure, family history of heart disease, high cholesterol and age (> 45 years for males and > 50 years for females) be considered for this important screening examination. With the chance of having a heart attack much greater then developing breast cancer and colon cancer, coronary artery screening should save many lives.

See more about this incredible breakthrough at http://www.westsidemedimaging.com/

From PR Newswire

Sunday, January 07, 2007

Guest Editorial

MARKETING AN OPERATION: CORONARY ARTERY BYPASS SURGERY

by Thomas A. Preston, MD

Dr. Thomas A. Preston is Professor of Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine and Chief of Cardiology at Pacific Medical Center, Seattle, Washington.

ABSTRACT: Coronary-bypass surgery is overused, frequently ineffective, and absurdly expensive. It is the epitome of modern medical technology, yet, as it is now practiced, its net effect on the nation's health is probably negative.

Preston TA: Marketing an operation: Coronary artery bypass surgery. J Holistic Med 1985;7(1):8-15.

Coronary-bypass surgery consumes more of our medical dollar than any other treatment or procedure. Although it is performed less frequently than the most common abdominal and gynecological operations, it is the leader in terms of equipment and personnel, hospital space, and total associated revenues. The operation is heralded by the popular press, aggrandized by the medical profession, and actively sought by the consuming public. It is the epitome of modern medical technology. Yet as it is now practiced, its net effect on the nation's health is probably negative. The operation does not cure patients, it is scandalously overused, and its high cost drains resources from other areas of need.

Fully half of the bypass operations performed in the United States are unnecessary. A decade of scientific study has shown that except in certain well-defined situations, bypass surgery does not save lives, or even prevent heart attacks: among patients who suffer from coronary-artery disease, those who are treated without surgery enjoy the same survival rates as those who undergo open-heart surgery. Yet many American physicians continue to prescribe surgery immediately upon the appearance of angina, or chest pain.

The concept of bypassing an obstructed artery to restore blood flow is simple enough for any eighth-grader to comprehend. In fact, for years before the advent of the coronary-bypass operation surgeons had performed similar operations on the larger arteries in the legs, using long, thin, artificial pipelines to carry blood from a point in front of to a point beyond an obstruction in the artery. Though the bypasses put into legs often became blocked themselves after a few years, such surgery produced two real benefits: it relieved pain in legs that were not getting enough blood, and it restored strength to legs that had been nearly useless. We can easily see why physicians thought, by extrapolation, that bypassing defective coronary arteries would produce equivalent results.

So strong was the analogy to leg surgery, and so compelling the hope of restoring diseased hearts, that physicians immediately embraced the idea of coronary-bypass surgery when the procedure was introduced in 1967 -- even though no evidence of its benefits was yet available. By 1969 the procedure was being performed at most of the nation's major medical centers. A few physicians cautioned against an untested and unproven therapy, but most simply took it on faith that the operation would relieve angina, prevent heart attacks, and prolong life. Calls for scientific studies of the operation's efficacy were rejected as unnecessary, and cardiologists and surgeons refused, as unethical, to withhold surgery from some patients so that comparative studies could be made, because they "knew" that those patients would die without the surgery. Meanwhile, proponents claimed in medical reports that patients who had bypass surgery were restored to normal, or even better than normal, life expectancy. Such was the depth of the conviction.

Of the 13,000 Americans on whom coronary-bypass operations were performed in 1970, at least 8% died as a result of the surgery. (At present, only 1% to 3% die, owing to technical refinements.) The assumption at the time was that a far greater number would have died if they had been given only the nonsurgical treatment when available. We will never know whether that was true, but in my opinion they would have lived longer, on the average, without the surgery. Meanwhile, surgical-training programs expanded rapidly, open-heart surgical facilities were developed in most large general hospitals, and the number of bypass operations performed each year grew steadily- reaching 60,000 by 1975.

Many of these were performed on patients who had what is known in the medical business as "unstable angina" -chest pain of recent onset or unusual severity. The category is broad enough to take in thousands of patients who reported no more than an increase in chest pain. Some physicians, mistakenly assuming that these patients were on the verge of death, declared them medical emergencies. Patients who reported a few episodes of chest discomfort, or who had chest pain when resting, were sent to surgery as soon as an operating room was available.

In 1977 the Veterans Administration reported a study showing that bypass surgery caused no decrease in average annual mortality among patients with ordinary angina unless they happened to be suffering from an obstruction of the left main coronary artery, a particularly severe form of heart disease. This was a scientific study, using controls for an impartial comparison, in contrast to many studies using no controls that had appeared in medical journals and that supported the practice. But bypass advocates blamed the results on the ineptitude of VA surgeons, even though the percentage of VA patients who died in surgery was below the national average,

In 1978 researchers for the National Institutes of Health completed a similar study, randomly assigning patients with unstable angina to either surgery or nonsurgery; their findings mirrored those of the VA experiment. No difference could be determined in rates of survival between the two groups-in other words, the cases were not real emergencies, as had been assumed, and heroic surgery was not saving lives. Again, the medical community largely ignored the results. Cardiologists kept prescribing immediate surgery for patients with unstable angina, and the explosive growth of the bypass business continued unabated. By 1983 the annual number of operations in the United States had soared to 191,000. Projections place the 1984 total at more than 200,000.

Patients who are given the bypass operation "to prolong life" fall into four major groups, only one of which has ever been shown to gain the promised result of such surgery. The first group is composed of those who suffer no symptoms at all. Such people may seem unlikely to end up on the operating table, but in fact many do. Typical would be the 55-year-old whose family doctor detects a slight abnormality on the electrocardiogram during a routine checkup. If an exercise stress test seems to confirm the abnormality, the doctor will refer the patient to a cardiologist for coronary angiography. And if the angiogram shows partial blockage of one or more of the three major arteries feeding the heart, the cardiologist may well recommend surgery, explaining to the patient that should one of these arteries become blocked, he'll have a heart attack and might die. So the patient submits to a bypass operation, after which he tells his friends at the health club how lucky he is to be alive. Those who see him jogging marvel at the sight. Unfortunately, not a shred of scientific evidence indicates that members of this group benefit from surgery; the operation may, in fact, cause such patients harm.

A second likely candidate for bypass surgery is the patient who has just suffered or recovered from a heart attack. Some cardiologists recommend the operation for all such patients, hoping that it will protect against another heart attack or sudden death. This policy is utterly unsupported by hard evidence. Two separate studies--one from the National Institutes of Health (1983) and one by researchers in New Zealand (1981)--have found no decrease in later heart attacks among patients who receive bypass surgery after suffering one. In neither study did patients who received the operation live longer than those who went without it.

A third contender for the scalpel is the patient who appears to be having a heart attack. The signs of an impending heart attack are notoriously unreliable --about two out of three patients admitted to hospitals for possible heart attacks turn out not to have had them. Bypass surgery cannot possibly prevent heart attacks in those who aren't having them. But what of those patients who are? Most physicians oppose surgery at such a critical stage, since new medicines for dissolving the clot that causes the heart attack are more effective and avoid the risks of surgery. Yet the operation is commonly performed in some communities. Whether patients who undergo surgery during a heart attack survive because of it or in spite of it is unknown.

About 11 % of all bypass operations are performed on heart patients for whom surgery clearly prolongs life -those suffering an obstruction of the left main artery. The National Institutes of Health published data in 1983—the most extensive and statistically meaningful to date in support of this finding.

Another 10% of patients, who have obstructions of all three major coronary arteries plus a weakened heart muscle, might have some extension of life owing to surgery, but we won't know if this is so until many more years have passed. The same study found that surgery does not prolong life for patients in the other categories. For the seven years since the VA broke the news, then, evidence has been mounting in opposition to the widely held belief that bypass surgery prevents heart attacks and saves lives. Given the number of historical precedents, we should not be surprised to find the medical profession attached to an incorrect belief; but why does the belief persist even after scientific studies demonstrate that it is wrong? As the authors of the latest NIH study concluded, with wonderful understatement, "when findings oppose generally accepted views, one can expect a large amount of criticism."

Mortality statistics aside, bypass surgery is widely believed to relieve chest pain, and this is now the reason most commonly given for performing the operation. Virtually all medical studies find an enhanced "quality of life" among patients who have had bypass surgery. In response to questionnaires, and especially to physicians' direct inquiries, they give responses like "I haven't felt so well in ten years" and "I can do four times as much as I could before the operation." I have patients whose improvement has been startling and is undoubtedly due to the surgery. Others are clearly worse off than they were before surgery. But the testimonials are troubling. Various operations and medicines have claimed equally dramatic results over the past four decades—only to be proved useless later on. Could bypass surgery be just another placebo? Quite possibly. Consider the testimony of patients whose vein grafts have ceased to function after the operation. More than a hundred such cases have been identified. Yet before finding out that their bypasses were blocked, these patients reported the same amelioration of symptoms as those who had had successful operations.

Whatever the proportion of actual to imagined benefit, the boom in coronary-bypass surgery created a need for more manpower in the operating room, which led to an increase in the number of slots in cardiac-surgery training programs. By the mid-1970s the number of surgeons trained to do bypass surgery was increasing at a rate of 10 to 15% each year, and as these new surgeons sought out suitable locales to practice their trade, the number of hospitals doing cardiac surgery just about doubled. Almost every small city in America now has a surgical team competing with the older referral centers, and any hospital aspiring to be a "complete medical center" seeks to have a team of its own -not just for prestige but because the operation is the biggest revenue-producer in the health field. As a result the procedure has taken on a life of its own. It is not so much the public's health as the profession's wealth that now dictates its use.

The average cardiac surgeon's fee in the United States is between $4,500 and $5,000 per bypass operation. The range is from $2,000 (for welfare patients done under contract) to more than $15,000. In high-rent districts fees routinely run from $7,000 to $10,000. Such information is not easy to come by: surgeons and hospital administrators are unapproachable about it. The only ones who know the exact figures are the patients who receive the bills and the insurance companies that pay them. The charges vary greatly, depending on the surgeon, the number of bypass grafts (generally each graft beyond the first one costs an additional $400 to $600), the hospital, and on the location (the difference may be as much as 100% from one part of the country to another).

A surgeon, moreover, might charge a well-off customer $6,000, while accepting $3,000 from a Medicare patient who has no supplemental insurance. Most physicians view this practice as generous and humanitarian, as a matter of scaling down the costs for those who can't afford to pay. Economists call it monopolistic price discrimination. In a nonmonopoly situation the seller offers the same price to all buyers, and profit margins tend to be narrow. But since physicians enjoy a monopoly, they can set any price they choose. The sliding scale not only creates a broader base of potential purchasers but also enables the seller to get the highest possible fee from each one.

Improved methods have reduced the amount of time necessary for the operation, allowing surgeons to perform five or six bypasses in a day while putting in less work overall. Yet fees per operation have escalated: a study of Blue Shield payments in the Washington, D.C., area found that allowances for coronary-bypass surgery rose by 75% from 1975 through 1978, In 1979, according to one national survey, most of the coronary-bypass operations in the United States were done by 677 surgeons, who averaged 137 operations that year. At 1984 prices, a surgeon performing that number of operations would collect fees of more than $600,000. And since most cardiac surgeons do other operations as well and receive other professional fees, their average income might be conservatively estimated at $750,000. These figures don't represent the surgeons who are in greatest demand or who charge the most; some surgeons operate three times a day, perhaps 700 times a year, using assistants to do the opening and closing. Their incomes are in the millions.

But the head surgeon isn't the only one with a direct economic stake in the bypass operation. In most hospitals one or two "assistant surgeons" each get an additional 20% of the head surgeon's fee-even though most of the tasks that they perform could be done by interns, nurses, or nonmedical assistants. And a surgeon receives fees for being on call, while a cardiologist performs a potentially hazardous procedure. If the surgeon isn't needed, he gets $500 to $800 for "availability." Nice work if you can get it.

Cardiologists also profit handsomely from the bypass operation, by doing the associated diagnostic work. The basic test is a cardiac catheterization, in which dye is injected into the coronary arteries to determine how severe and how many are the obstructions. The professional fee averages $800, not quite in the surgeon's ballpark; but a cardiologist may do two or three catheterizations for every patient sent to surgery- and performing even five a week can generate an annual income of $184,000, while consuming only a fifth of his time. Anesthesiologists, who also derive fees from bypass surgery, tend to have complicated schedules based on time spent, and their fees vary from place to place. But the national average is about $1,250 per case, and since responsibilities before and after the operation are minimal, the average anesthesiologist can handle two cases everyday with ease.

Then there's the hospital. For the diagnostic cardiac catheterization alone, lab and technicians' fees average $1,100. Charges for other tests and for hospital stay are additional (intensive-care units average $1,000 a day, plus extras). Operating-room fees (for nurses, technicians, equipment, and supplies) run from $5,0OO to $8000. The usual blood tests, X-rays, and scans bring the total costs for one bypass operation to about $25,000. Of this, various physicians fees are about $7,500, or nearly 30% of the total. Again, these figures are averages; in some cases, the total charges exceed $100,000.

With prices like these, the patients who actually get the operation are not necessarily those who most need it but rather those who have the best access to the health-care system: the typical bypass patient is a 53-year-old white male with private health insurance.

The fact that 79 % of all bypass recipients are men is usually explained by the higher incidence of coronary-artery disease among males and by generally poorer results of such operations among females (whose arteries tend to be smaller and thus larder to bypass. The race difference, on the other hand, has nothing to do with biology. Age-adjusted mortality statistics suggest that coronary-artery disease is just as prevalent in blacks as in whites; in fact, angina tends to disable blacks earlier in life than it does whites. Yet whites receive 97% of all bypass operations performed in the United States. The relative youthfulness of the bypass population is equally difficult to explain in purely medical terms. The median age at which patients first develop angina or suffer a heart attack is 65; the median age for death from coronary-artery disease is 75. Yet only 25 % of all bypass operations are performed on persons age 65 or older. The inescapable conclusion is that the poor, the nonwhite, and the elderly receive a disproportionately low share of this medical service.

This is not to say that age and social conditions account for all variation in the use of bypass surgery; a patient's chances of getting the operation also vary according to where he lives and how his medical care is financed. In the United States bypass surgery is performed twice as often as it is in Canada and Australia, and more than four as often as in Western Europe, despite similar demographics and social conditions. And within the United States, patients served by prepaid physician's groups receive the operation less than half as often as those whose doctors are paid on a fee-for-service basis. The difference in financial incentives is impossible to ignore. Canadian surgeons are paid about $1,100 per operation --roughly one fourth of what their U.S. counterparts make. In Europe and Australia most physicians receive salaries rather than piece rates. So do the surgeons and cardiologists working under prepaid plans in the United States. Would the rest of America's doctors be doing such a vast number of operations if the average fee were cut from $4,500 to $450? I doubt it.

Surgeons invariably maintain that the decision to operate on an individual patient is based on medical factors rather than on an ability to pay. In fact, they say, "We're only operating on patients whom cardiologists tell us to operate on." True, almost all patients are funneled to cardiac surgery through a cardiologist. But the cardiologist is subject to countless nonmedical pushes and pulls. Some of these come from the patient himself: patients generally want something done, as do referring physicians, and if a cardiologist wants referrals, he will arrange to have done what can be done. Most of a cardiologist's business today is with patients who have coronary-artery disease. The disease can be diagnosed by simple questioning, and drug treatment requires no special testing. The expensive tests that produce most of a cardiologist's income (such as scans and cardiac catheterizations) are used primarily to see if surgery is possible, and to give the surgeon the information necessary to perform it. The cardiologist and the cardiac surgeon are thus interdependent in their work, and each influences the other. Both have strong financial incentives to promote bypass surgery.

Even if fees have little direct bearing on individual decisions to operate, they clearly influence physicians to specialize in fields where they can collect high fees without a sense of conflict. If this is not so, why are so many physicians in training for a lucrative field like cardiac surgery, while so few are preparing to treat hypertension in the inner cities, to fill voids in rural areas, and to provide primary care for the elderly?

Physicians and consumers of medical care alike should have two major concerns about how bypass surgery is used. First, we should be concerned about individual patients and about whether current practice is producing optimal results. Do patients really get enough information to give informed consent for the operation? Do they realize that, on the average, the operation does not prolong life or prevent heart attacks? Do they know of the dangers associated with the operation itself, including a 5% risk of heart attack on the table, a 2% risk of dying, and about a 10% risk of serious complication, such as stroke, weakening of the heart muscle, or infection? Are they aware that unless they are experiencing frequent or severe angina, they may suffer net harm from the operation? Do patients understand that the operation does not cure them but only palliates, and that the average patient may need a second operation within seven years, which will be riskier and less successful than the first? When a patient is told he needs bypass surgery, are his options really explained to him? Does he realize that expert advice may vary according to what a given expert stands to gain from the operation?

The second major concern is societal. We are in an era of budget deficits and economic retrenchment, an era in which spending more on one medical option means spending less on another. We will devote approximately $5 billion to bypass surgery in the United States this year, at a time when health benefits for the elderly are being reduced and when approximately 25 million Americans lack health insurance or other means to pay for medical care. As a society we must ask ourselves whether this distribution of resources is fair or appropriate. We now spend more on coronary-bypass operation than we do on medical research and prevention of heart disease combined. If we could divert half of what we spend on this one treatment into programs to help people stop smoking, lower cholesterol in their diets, reduce hypertension, and exercise more, the benefit would be greater than if we doubled our spending on treatment after the disease strikes.

by Thomas A. Preston, MD

Dr. Thomas A. Preston is Professor of Medicine at the University of Washington School of Medicine and Chief of Cardiology at Pacific Medical Center, Seattle, Washington.

ABSTRACT: Coronary-bypass surgery is overused, frequently ineffective, and absurdly expensive. It is the epitome of modern medical technology, yet, as it is now practiced, its net effect on the nation's health is probably negative.

Preston TA: Marketing an operation: Coronary artery bypass surgery. J Holistic Med 1985;7(1):8-15.

Coronary-bypass surgery consumes more of our medical dollar than any other treatment or procedure. Although it is performed less frequently than the most common abdominal and gynecological operations, it is the leader in terms of equipment and personnel, hospital space, and total associated revenues. The operation is heralded by the popular press, aggrandized by the medical profession, and actively sought by the consuming public. It is the epitome of modern medical technology. Yet as it is now practiced, its net effect on the nation's health is probably negative. The operation does not cure patients, it is scandalously overused, and its high cost drains resources from other areas of need.

Fully half of the bypass operations performed in the United States are unnecessary. A decade of scientific study has shown that except in certain well-defined situations, bypass surgery does not save lives, or even prevent heart attacks: among patients who suffer from coronary-artery disease, those who are treated without surgery enjoy the same survival rates as those who undergo open-heart surgery. Yet many American physicians continue to prescribe surgery immediately upon the appearance of angina, or chest pain.

The concept of bypassing an obstructed artery to restore blood flow is simple enough for any eighth-grader to comprehend. In fact, for years before the advent of the coronary-bypass operation surgeons had performed similar operations on the larger arteries in the legs, using long, thin, artificial pipelines to carry blood from a point in front of to a point beyond an obstruction in the artery. Though the bypasses put into legs often became blocked themselves after a few years, such surgery produced two real benefits: it relieved pain in legs that were not getting enough blood, and it restored strength to legs that had been nearly useless. We can easily see why physicians thought, by extrapolation, that bypassing defective coronary arteries would produce equivalent results.

So strong was the analogy to leg surgery, and so compelling the hope of restoring diseased hearts, that physicians immediately embraced the idea of coronary-bypass surgery when the procedure was introduced in 1967 -- even though no evidence of its benefits was yet available. By 1969 the procedure was being performed at most of the nation's major medical centers. A few physicians cautioned against an untested and unproven therapy, but most simply took it on faith that the operation would relieve angina, prevent heart attacks, and prolong life. Calls for scientific studies of the operation's efficacy were rejected as unnecessary, and cardiologists and surgeons refused, as unethical, to withhold surgery from some patients so that comparative studies could be made, because they "knew" that those patients would die without the surgery. Meanwhile, proponents claimed in medical reports that patients who had bypass surgery were restored to normal, or even better than normal, life expectancy. Such was the depth of the conviction.

Of the 13,000 Americans on whom coronary-bypass operations were performed in 1970, at least 8% died as a result of the surgery. (At present, only 1% to 3% die, owing to technical refinements.) The assumption at the time was that a far greater number would have died if they had been given only the nonsurgical treatment when available. We will never know whether that was true, but in my opinion they would have lived longer, on the average, without the surgery. Meanwhile, surgical-training programs expanded rapidly, open-heart surgical facilities were developed in most large general hospitals, and the number of bypass operations performed each year grew steadily- reaching 60,000 by 1975.

Many of these were performed on patients who had what is known in the medical business as "unstable angina" -chest pain of recent onset or unusual severity. The category is broad enough to take in thousands of patients who reported no more than an increase in chest pain. Some physicians, mistakenly assuming that these patients were on the verge of death, declared them medical emergencies. Patients who reported a few episodes of chest discomfort, or who had chest pain when resting, were sent to surgery as soon as an operating room was available.

In 1977 the Veterans Administration reported a study showing that bypass surgery caused no decrease in average annual mortality among patients with ordinary angina unless they happened to be suffering from an obstruction of the left main coronary artery, a particularly severe form of heart disease. This was a scientific study, using controls for an impartial comparison, in contrast to many studies using no controls that had appeared in medical journals and that supported the practice. But bypass advocates blamed the results on the ineptitude of VA surgeons, even though the percentage of VA patients who died in surgery was below the national average,

In 1978 researchers for the National Institutes of Health completed a similar study, randomly assigning patients with unstable angina to either surgery or nonsurgery; their findings mirrored those of the VA experiment. No difference could be determined in rates of survival between the two groups-in other words, the cases were not real emergencies, as had been assumed, and heroic surgery was not saving lives. Again, the medical community largely ignored the results. Cardiologists kept prescribing immediate surgery for patients with unstable angina, and the explosive growth of the bypass business continued unabated. By 1983 the annual number of operations in the United States had soared to 191,000. Projections place the 1984 total at more than 200,000.

Patients who are given the bypass operation "to prolong life" fall into four major groups, only one of which has ever been shown to gain the promised result of such surgery. The first group is composed of those who suffer no symptoms at all. Such people may seem unlikely to end up on the operating table, but in fact many do. Typical would be the 55-year-old whose family doctor detects a slight abnormality on the electrocardiogram during a routine checkup. If an exercise stress test seems to confirm the abnormality, the doctor will refer the patient to a cardiologist for coronary angiography. And if the angiogram shows partial blockage of one or more of the three major arteries feeding the heart, the cardiologist may well recommend surgery, explaining to the patient that should one of these arteries become blocked, he'll have a heart attack and might die. So the patient submits to a bypass operation, after which he tells his friends at the health club how lucky he is to be alive. Those who see him jogging marvel at the sight. Unfortunately, not a shred of scientific evidence indicates that members of this group benefit from surgery; the operation may, in fact, cause such patients harm.

A second likely candidate for bypass surgery is the patient who has just suffered or recovered from a heart attack. Some cardiologists recommend the operation for all such patients, hoping that it will protect against another heart attack or sudden death. This policy is utterly unsupported by hard evidence. Two separate studies--one from the National Institutes of Health (1983) and one by researchers in New Zealand (1981)--have found no decrease in later heart attacks among patients who receive bypass surgery after suffering one. In neither study did patients who received the operation live longer than those who went without it.

A third contender for the scalpel is the patient who appears to be having a heart attack. The signs of an impending heart attack are notoriously unreliable --about two out of three patients admitted to hospitals for possible heart attacks turn out not to have had them. Bypass surgery cannot possibly prevent heart attacks in those who aren't having them. But what of those patients who are? Most physicians oppose surgery at such a critical stage, since new medicines for dissolving the clot that causes the heart attack are more effective and avoid the risks of surgery. Yet the operation is commonly performed in some communities. Whether patients who undergo surgery during a heart attack survive because of it or in spite of it is unknown.

About 11 % of all bypass operations are performed on heart patients for whom surgery clearly prolongs life -those suffering an obstruction of the left main artery. The National Institutes of Health published data in 1983—the most extensive and statistically meaningful to date in support of this finding.

Another 10% of patients, who have obstructions of all three major coronary arteries plus a weakened heart muscle, might have some extension of life owing to surgery, but we won't know if this is so until many more years have passed. The same study found that surgery does not prolong life for patients in the other categories. For the seven years since the VA broke the news, then, evidence has been mounting in opposition to the widely held belief that bypass surgery prevents heart attacks and saves lives. Given the number of historical precedents, we should not be surprised to find the medical profession attached to an incorrect belief; but why does the belief persist even after scientific studies demonstrate that it is wrong? As the authors of the latest NIH study concluded, with wonderful understatement, "when findings oppose generally accepted views, one can expect a large amount of criticism."

Mortality statistics aside, bypass surgery is widely believed to relieve chest pain, and this is now the reason most commonly given for performing the operation. Virtually all medical studies find an enhanced "quality of life" among patients who have had bypass surgery. In response to questionnaires, and especially to physicians' direct inquiries, they give responses like "I haven't felt so well in ten years" and "I can do four times as much as I could before the operation." I have patients whose improvement has been startling and is undoubtedly due to the surgery. Others are clearly worse off than they were before surgery. But the testimonials are troubling. Various operations and medicines have claimed equally dramatic results over the past four decades—only to be proved useless later on. Could bypass surgery be just another placebo? Quite possibly. Consider the testimony of patients whose vein grafts have ceased to function after the operation. More than a hundred such cases have been identified. Yet before finding out that their bypasses were blocked, these patients reported the same amelioration of symptoms as those who had had successful operations.

Whatever the proportion of actual to imagined benefit, the boom in coronary-bypass surgery created a need for more manpower in the operating room, which led to an increase in the number of slots in cardiac-surgery training programs. By the mid-1970s the number of surgeons trained to do bypass surgery was increasing at a rate of 10 to 15% each year, and as these new surgeons sought out suitable locales to practice their trade, the number of hospitals doing cardiac surgery just about doubled. Almost every small city in America now has a surgical team competing with the older referral centers, and any hospital aspiring to be a "complete medical center" seeks to have a team of its own -not just for prestige but because the operation is the biggest revenue-producer in the health field. As a result the procedure has taken on a life of its own. It is not so much the public's health as the profession's wealth that now dictates its use.

The average cardiac surgeon's fee in the United States is between $4,500 and $5,000 per bypass operation. The range is from $2,000 (for welfare patients done under contract) to more than $15,000. In high-rent districts fees routinely run from $7,000 to $10,000. Such information is not easy to come by: surgeons and hospital administrators are unapproachable about it. The only ones who know the exact figures are the patients who receive the bills and the insurance companies that pay them. The charges vary greatly, depending on the surgeon, the number of bypass grafts (generally each graft beyond the first one costs an additional $400 to $600), the hospital, and on the location (the difference may be as much as 100% from one part of the country to another).

A surgeon, moreover, might charge a well-off customer $6,000, while accepting $3,000 from a Medicare patient who has no supplemental insurance. Most physicians view this practice as generous and humanitarian, as a matter of scaling down the costs for those who can't afford to pay. Economists call it monopolistic price discrimination. In a nonmonopoly situation the seller offers the same price to all buyers, and profit margins tend to be narrow. But since physicians enjoy a monopoly, they can set any price they choose. The sliding scale not only creates a broader base of potential purchasers but also enables the seller to get the highest possible fee from each one.

Improved methods have reduced the amount of time necessary for the operation, allowing surgeons to perform five or six bypasses in a day while putting in less work overall. Yet fees per operation have escalated: a study of Blue Shield payments in the Washington, D.C., area found that allowances for coronary-bypass surgery rose by 75% from 1975 through 1978, In 1979, according to one national survey, most of the coronary-bypass operations in the United States were done by 677 surgeons, who averaged 137 operations that year. At 1984 prices, a surgeon performing that number of operations would collect fees of more than $600,000. And since most cardiac surgeons do other operations as well and receive other professional fees, their average income might be conservatively estimated at $750,000. These figures don't represent the surgeons who are in greatest demand or who charge the most; some surgeons operate three times a day, perhaps 700 times a year, using assistants to do the opening and closing. Their incomes are in the millions.

But the head surgeon isn't the only one with a direct economic stake in the bypass operation. In most hospitals one or two "assistant surgeons" each get an additional 20% of the head surgeon's fee-even though most of the tasks that they perform could be done by interns, nurses, or nonmedical assistants. And a surgeon receives fees for being on call, while a cardiologist performs a potentially hazardous procedure. If the surgeon isn't needed, he gets $500 to $800 for "availability." Nice work if you can get it.

Cardiologists also profit handsomely from the bypass operation, by doing the associated diagnostic work. The basic test is a cardiac catheterization, in which dye is injected into the coronary arteries to determine how severe and how many are the obstructions. The professional fee averages $800, not quite in the surgeon's ballpark; but a cardiologist may do two or three catheterizations for every patient sent to surgery- and performing even five a week can generate an annual income of $184,000, while consuming only a fifth of his time. Anesthesiologists, who also derive fees from bypass surgery, tend to have complicated schedules based on time spent, and their fees vary from place to place. But the national average is about $1,250 per case, and since responsibilities before and after the operation are minimal, the average anesthesiologist can handle two cases everyday with ease.

Then there's the hospital. For the diagnostic cardiac catheterization alone, lab and technicians' fees average $1,100. Charges for other tests and for hospital stay are additional (intensive-care units average $1,000 a day, plus extras). Operating-room fees (for nurses, technicians, equipment, and supplies) run from $5,0OO to $8000. The usual blood tests, X-rays, and scans bring the total costs for one bypass operation to about $25,000. Of this, various physicians fees are about $7,500, or nearly 30% of the total. Again, these figures are averages; in some cases, the total charges exceed $100,000.

With prices like these, the patients who actually get the operation are not necessarily those who most need it but rather those who have the best access to the health-care system: the typical bypass patient is a 53-year-old white male with private health insurance.

The fact that 79 % of all bypass recipients are men is usually explained by the higher incidence of coronary-artery disease among males and by generally poorer results of such operations among females (whose arteries tend to be smaller and thus larder to bypass. The race difference, on the other hand, has nothing to do with biology. Age-adjusted mortality statistics suggest that coronary-artery disease is just as prevalent in blacks as in whites; in fact, angina tends to disable blacks earlier in life than it does whites. Yet whites receive 97% of all bypass operations performed in the United States. The relative youthfulness of the bypass population is equally difficult to explain in purely medical terms. The median age at which patients first develop angina or suffer a heart attack is 65; the median age for death from coronary-artery disease is 75. Yet only 25 % of all bypass operations are performed on persons age 65 or older. The inescapable conclusion is that the poor, the nonwhite, and the elderly receive a disproportionately low share of this medical service.

This is not to say that age and social conditions account for all variation in the use of bypass surgery; a patient's chances of getting the operation also vary according to where he lives and how his medical care is financed. In the United States bypass surgery is performed twice as often as it is in Canada and Australia, and more than four as often as in Western Europe, despite similar demographics and social conditions. And within the United States, patients served by prepaid physician's groups receive the operation less than half as often as those whose doctors are paid on a fee-for-service basis. The difference in financial incentives is impossible to ignore. Canadian surgeons are paid about $1,100 per operation --roughly one fourth of what their U.S. counterparts make. In Europe and Australia most physicians receive salaries rather than piece rates. So do the surgeons and cardiologists working under prepaid plans in the United States. Would the rest of America's doctors be doing such a vast number of operations if the average fee were cut from $4,500 to $450? I doubt it.

Surgeons invariably maintain that the decision to operate on an individual patient is based on medical factors rather than on an ability to pay. In fact, they say, "We're only operating on patients whom cardiologists tell us to operate on." True, almost all patients are funneled to cardiac surgery through a cardiologist. But the cardiologist is subject to countless nonmedical pushes and pulls. Some of these come from the patient himself: patients generally want something done, as do referring physicians, and if a cardiologist wants referrals, he will arrange to have done what can be done. Most of a cardiologist's business today is with patients who have coronary-artery disease. The disease can be diagnosed by simple questioning, and drug treatment requires no special testing. The expensive tests that produce most of a cardiologist's income (such as scans and cardiac catheterizations) are used primarily to see if surgery is possible, and to give the surgeon the information necessary to perform it. The cardiologist and the cardiac surgeon are thus interdependent in their work, and each influences the other. Both have strong financial incentives to promote bypass surgery.

Even if fees have little direct bearing on individual decisions to operate, they clearly influence physicians to specialize in fields where they can collect high fees without a sense of conflict. If this is not so, why are so many physicians in training for a lucrative field like cardiac surgery, while so few are preparing to treat hypertension in the inner cities, to fill voids in rural areas, and to provide primary care for the elderly?

Physicians and consumers of medical care alike should have two major concerns about how bypass surgery is used. First, we should be concerned about individual patients and about whether current practice is producing optimal results. Do patients really get enough information to give informed consent for the operation? Do they realize that, on the average, the operation does not prolong life or prevent heart attacks? Do they know of the dangers associated with the operation itself, including a 5% risk of heart attack on the table, a 2% risk of dying, and about a 10% risk of serious complication, such as stroke, weakening of the heart muscle, or infection? Are they aware that unless they are experiencing frequent or severe angina, they may suffer net harm from the operation? Do patients understand that the operation does not cure them but only palliates, and that the average patient may need a second operation within seven years, which will be riskier and less successful than the first? When a patient is told he needs bypass surgery, are his options really explained to him? Does he realize that expert advice may vary according to what a given expert stands to gain from the operation?

The second major concern is societal. We are in an era of budget deficits and economic retrenchment, an era in which spending more on one medical option means spending less on another. We will devote approximately $5 billion to bypass surgery in the United States this year, at a time when health benefits for the elderly are being reduced and when approximately 25 million Americans lack health insurance or other means to pay for medical care. As a society we must ask ourselves whether this distribution of resources is fair or appropriate. We now spend more on coronary-bypass operation than we do on medical research and prevention of heart disease combined. If we could divert half of what we spend on this one treatment into programs to help people stop smoking, lower cholesterol in their diets, reduce hypertension, and exercise more, the benefit would be greater than if we doubled our spending on treatment after the disease strikes.

Saturday, January 06, 2007

Dr. Wayne's Memorial Service

I received the following letter today:

Dear Patients and Friends: