During seven years of not feeling well, Silvia Rizzuto never thought about her heart.

The middle-aged mother of two chalked up her fatigue, her shortness of breath, to stress and being overweight.

Then she got sicker – constantly feeling tired, occasionally blanking out for a second – and her doctor finally referred her to a cardiologist.

Her life was more imperiled than she ever realized. While undergoing tests, Rizzuto suffered cardiac arrest.

She was revived and diagnosed with ventricular tachycardia, a rapid heart beat that can cause sudden cardiac death – she had a defibrillator implanted in her chest. Rizutto also had hypertrophic obstructive cardiomyopathy – part of her heart had thickened, impeding blood flow. Last June she underwent more than four hours of open-heart surgery to carve away part of the thickened muscle.

"I always worried about breast cancer and carefully checked myself," says Rizzuto, 49. "I knew nothing about heart disease. It came as a very big shock."

Cardiologists hear this from women all the time. But more Canadian women die every year from cardiovascular disease – 36,695 deaths in 2004 – than from all the cancers combined: 32,458 women were claimed by cancers in 2004. The news gets worse. For the first time, cardiovascular disease is now an equal opportunity killer, felling nearly as many women as men, according to a report this year from the Heart and Stroke Foundation of Canada. The report also pointed to an alarming gender gap: women are less likely than men to receive the right treatment and more likely to die. It has prompted Heart and Stroke to explore a national campaign to highlight women and heart disease, modeled after a successful six-year awareness blitz in the U.S.

"We need to do a better job marketing the impact of cardiovascular disease in women," says Heather Ross, medical director of cardiac transplants at Toronto General Hospital. "It's absolutely a hot topic."

The topic earned headlines last month when Canadian singer Jann Arden was hospitalized with takotsubo, or stress-induced cardiomyopathy – also known as broken heart syndrome. The disorder, believed to be more prevalent in women, may first appear with sudden chest pain, and causes part of the heart to bulge.

Last month, the Canadian Medical Association Journal devoted a special supplement to sex-specific issues related to cardiovascular disease. "We've summarized what's known and identified the knowledge gaps," says Louise Pilote, principal investigator on GENESIS, a five-year project involving 40 Canadian researchers studying sex and gender factors of heart disease and stroke.

One key knowledge gap: Doctors can't fully explain why the incidence and mortality of heart disease and stroke is decreasing among men and not women.

"Female patients are slightly older and sicker," says Toronto cardiologist Beth Abramson, "but even when you correct for age, it doesn't explain it."

Women's hearts tend to be protected before menopause, possibly through the effects of estrogen. After menopause, their risk of heart disease and stroke rises. The average age for a heart attack in women is 65, compared to 55 for men.

The misconception that cardiac disease is a man's problem is a bias held by both patients and some medical professionals, says Leonard Sternberg, director of cardiology at Women's College Hospital. "Women need to be more pro-active about their hearts."

That gender bias could keep a woman's heart disease from being diagnosed early – or even prevented. There's even been confusion about the signs of a female heart attack. Doctors used to believe women presented different symptoms than men, but now that's doubted, according to cardiologist Abramson, spokesperson for the Heart and Stroke Foundation. "Women may just describe the symptoms differently," she says.

While about 70 per cent of heart attacks cause chest pain in both male and female victim, 30 per cent do not, says cardiologist Sharonne Hayes, director of the Women's Heart Clinic at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. Instead, they experience a mix of symptoms – shortness of breath, gastrointestinal upset, loss of consciousness, excessive sweating.

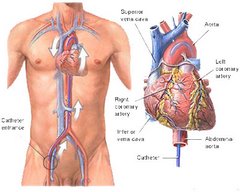

Women are also less likely to be treated by a cardiologist or receive coronary artery bypass graft surgey or angioplasty (to reopen blocked arteries) than men, according to the recent Heart and Stroke Foundation report.

"The advances in the treatment of cardiovascular diseases have been fairly dramatic," says Hayes. "If you're not seeing a specialist, you're not being offered the treatment you're eligible for."

Another hurdle for women has been their low numbers in cardiovascular clinical trials, at about only 20 per cent, says cardiologist Ross, even though women account for 62 percent of deaths by heart failure. The disease is more common in the elderly, and that means women since human females outlive males.

Scientists don't yet fully understand what biological gender differences might affect heart disease and treatment. "We're on the cusp of learning a whole lot more, of better understanding the role of hormones," says Hayes.

For example, the HRT results of the landmark Women's Health Initiative Study surprised the world's medical community in 2002. Once thought to protect post-menopausal women from cardiovascular disease, hormone replacement therapy appeared, instead, to be linked to increased risk of heart disease and stroke.

In her animal research, Carin Wittnich, director of the cardiovascular sciences collaborative program at UofT, has found that estrogen is a "double-edged sword."While it helps protect healthy female hearts, estrogen may hurt a diseased heart before menopause. "It's not straightforward," says Wittnich. "We're slowly peeling each layer, like an onion."

What is more straightforward is how to keep a heart healthy. The majority of cardiovascular disease cases could be prevented, says the Mayo Clinic's Hayes. Notwithstanding family history, people can control risk factors such as high blood pressure and cholesterol, smoking, obesity and a sedentary lifestyle. Diabetes is of particular concern: It increases the chances of cardiovascular disease by 70 per cent in women, compared to 40 per cent in men, says TGH cardiologist Ross.

Heart patient Rizzuto changed her attitude, with the help of the cardiac rehabilitation program at Women's College. "It made me realize I need to take time for myself," says Rizzuto. "Before it was always about family, never me."

The rehab program, which includes educational sessions and personal support, is the sole women-only program in North America, says Jennifer Price, nurse practitioner in cardiology at Women's College. Rizzuto works out on the hospital's exercise equipment twice weekly and meets with a dietician about weight loss. She's joined a fitness centre to keep exercising when her six months in rehab ends. She's also enjoying long walks in her neighbourhood. "I'm definitely more energetic," smiles Rizzuto, using the step machine. "I feel alive now."

From the Toronto Star

No comments:

Post a Comment